TANTE TRUUS – To Vienna

Unknown photographer

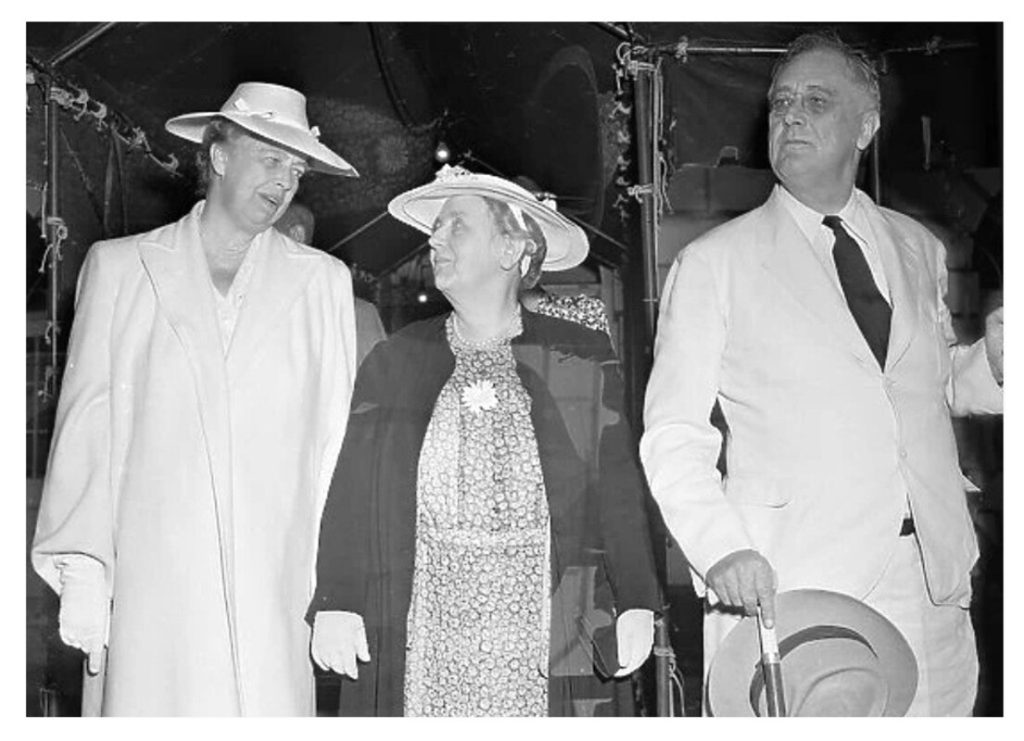

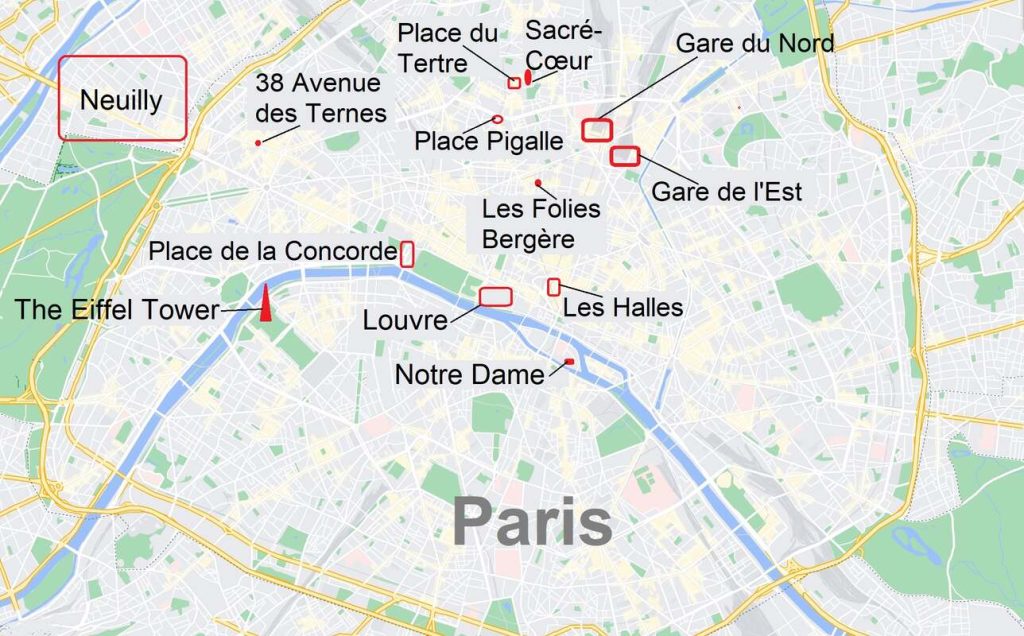

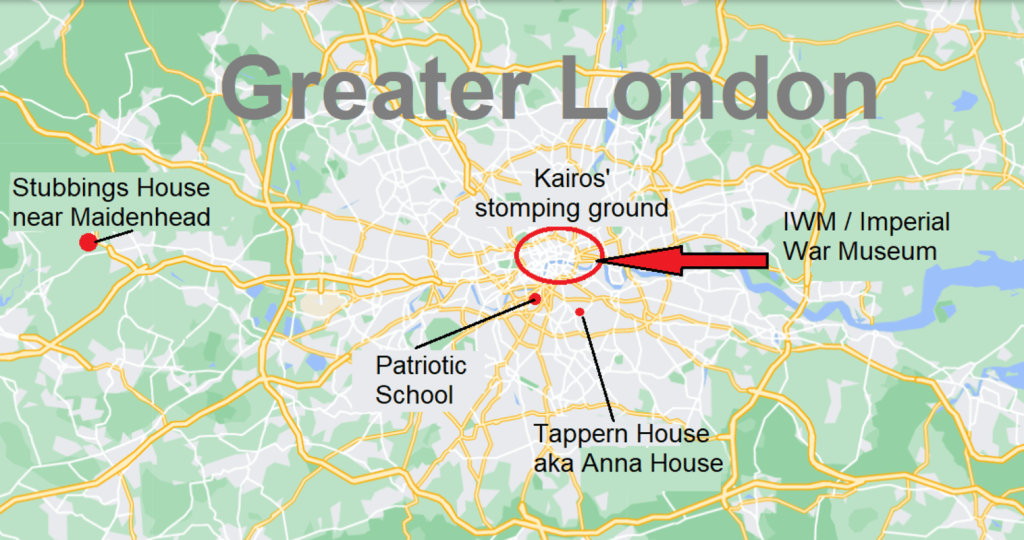

Truus Wijsmuller (pronounced like /Truce Weiss-mal-lar/) was an amazing Dutch social activist, politician, and Resistance fighter now best known for defying Adolph Eichmann and leading the “Kindertransports.” After several devastating miscarriages, Mrs. Wijsmuller decided to do what the doctor had advised and get involved in charities and committee work, and did she ever!

While she rescued far more Jews than Oskar Schindler and Sir Nicholas Winton combined, her work remained practically unknown even in the Netherlands until about 2010. In 1961, a short, little-known Dutch book based on interviews with Wijsmuller by C.L. Vrooland appeared as No Time for Tears. Mrs. Wijsmuller was a protagonist in American writer Meg Waite Clayton’s novel The Last Train to London, which was published in 2019. Then finally in 2020, two Dutch efforts came to fruition; both a large statue of Mrs. Wijsmuller surrounded by children was revealed in her native city of Alkmaar and the documentary Truus’ Children was released.

Fact or Fiction: Apart from her relationship with the fictitious Edeline Adler and Lettie Keizer, everything about Mrs. Wijsmuller is as accurate as possible. Her conversation with Eichmann is loosely based on her own testimony in interviews and as narrated by C.L. Vrooland in No Time for Tears.

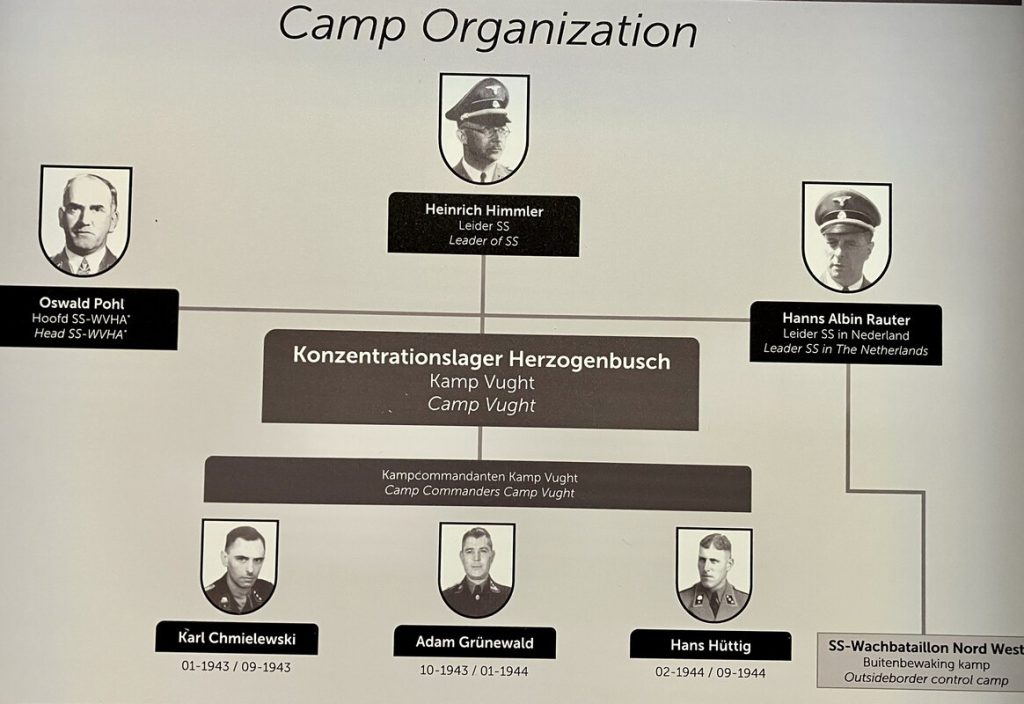

Unknown artist

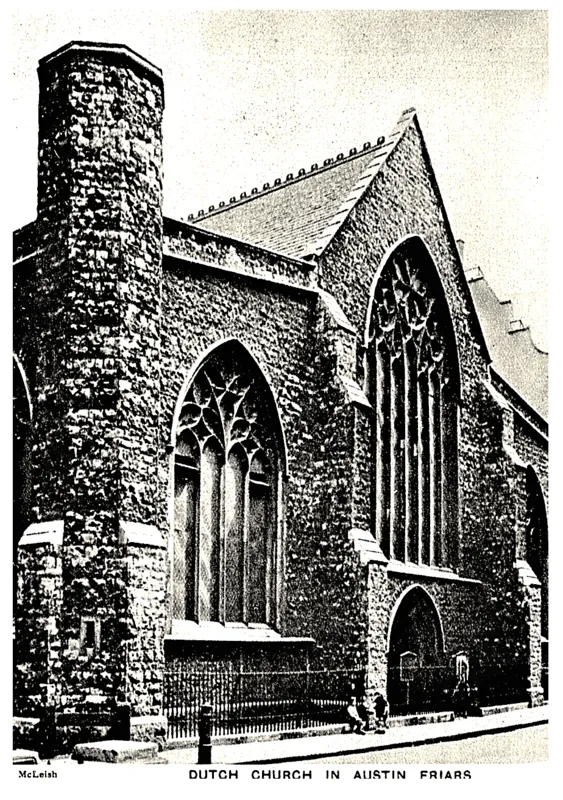

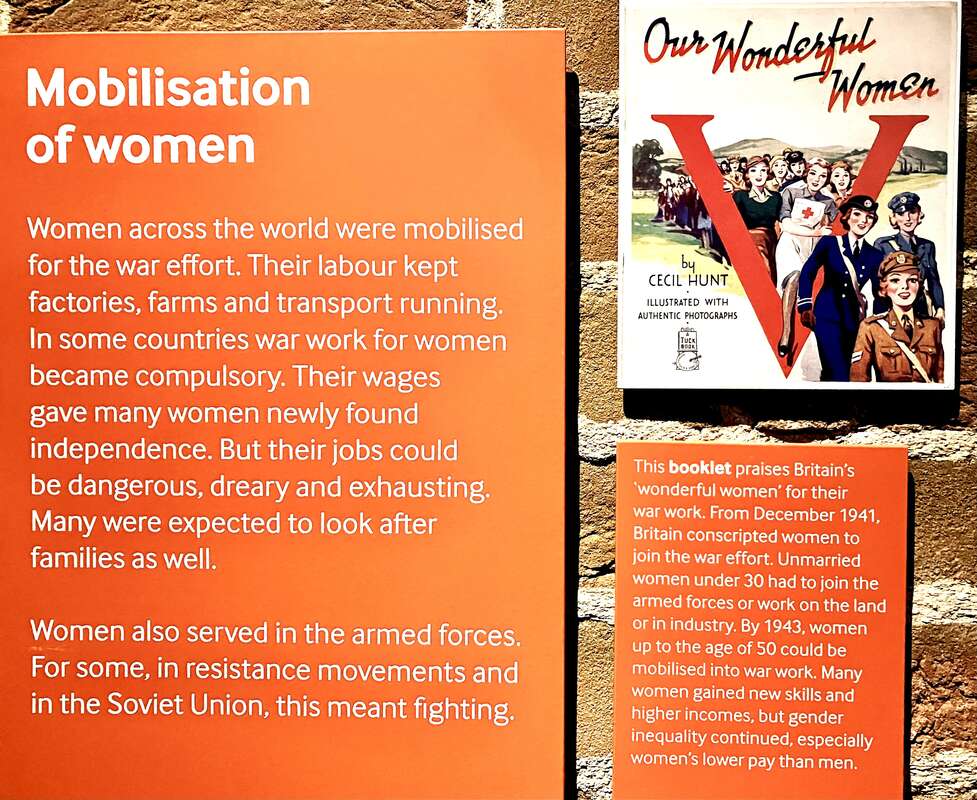

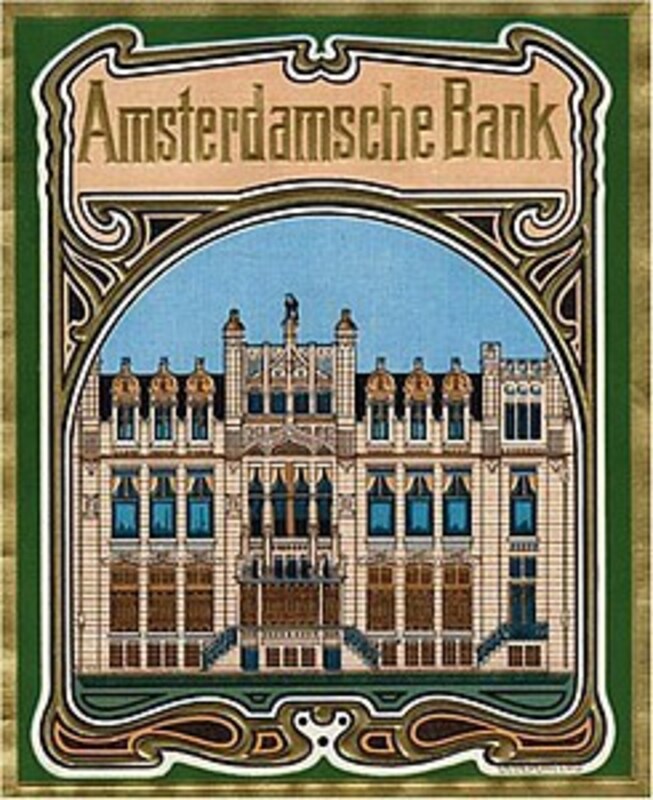

At a meeting at the Amsterdam Bank, Truus Wijsmuller who was the only woman in the room, was asked by the men to go talk to a certain doctor Eichmann to see if she could arrange for larger-scale evacuations of Jewish children than she had been handling on her own.

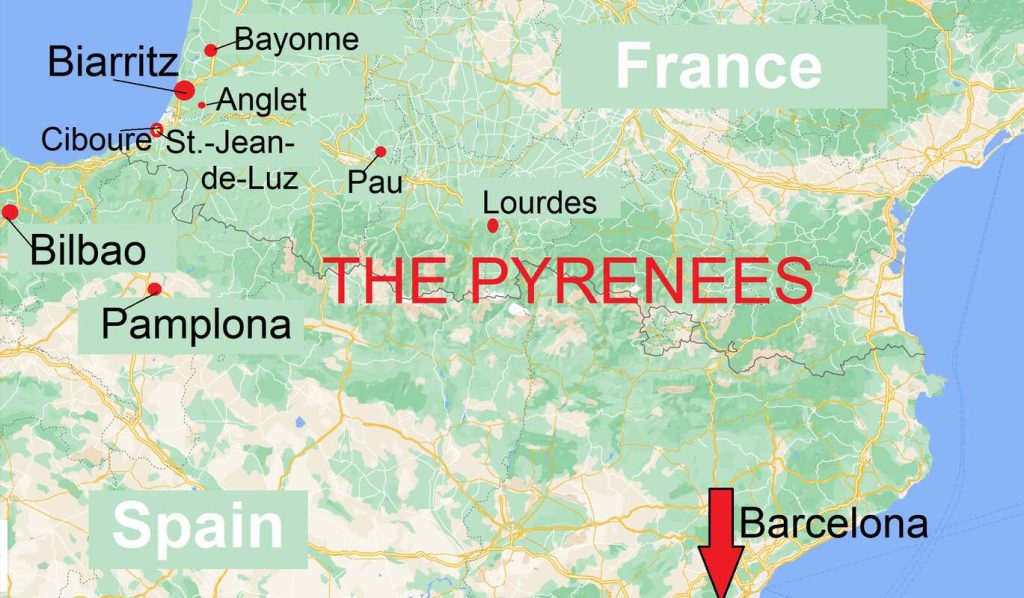

Perhaps they asked her, the only woman because she had already worked with the “Kultusgemeinde” (/kool-toos-ghu-meynda/) of Munich and Berlin, Jewish organizations whose members often asked her to smuggle their children out of Germany. Or maybe it had to do with her reputation of a woman who could get things done, or put more negatively by some; she was a “steamroller.” Or worse yet, she wondered if she had been chosen because she had no children and thus, would not object to missing the children’s Feast of Saint Nicholas on December fifth. Instead of celebrating that Dutch holiday with her husband at home, Mrs. Wijsmuller was alone in Vienna where pushy pro-Nazis wanted her to contribute to their fundraiser…

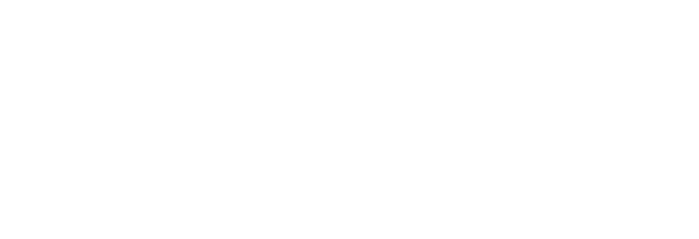

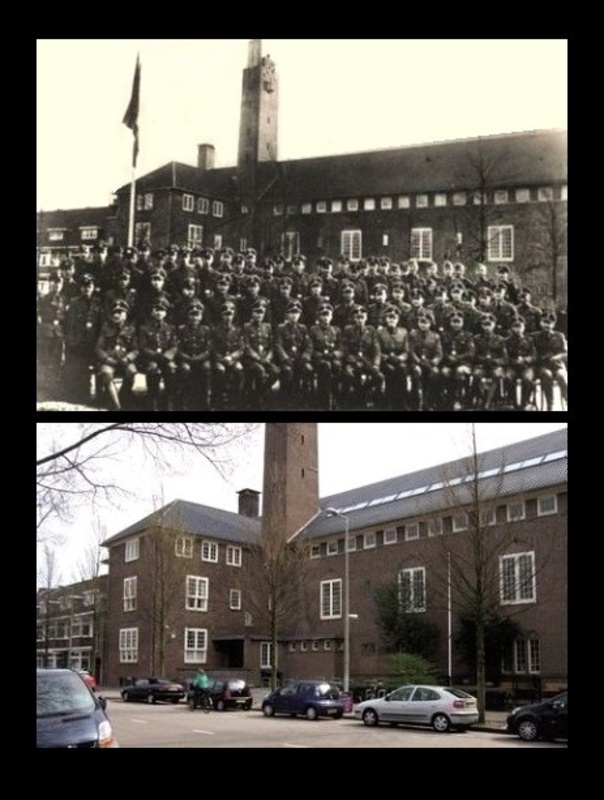

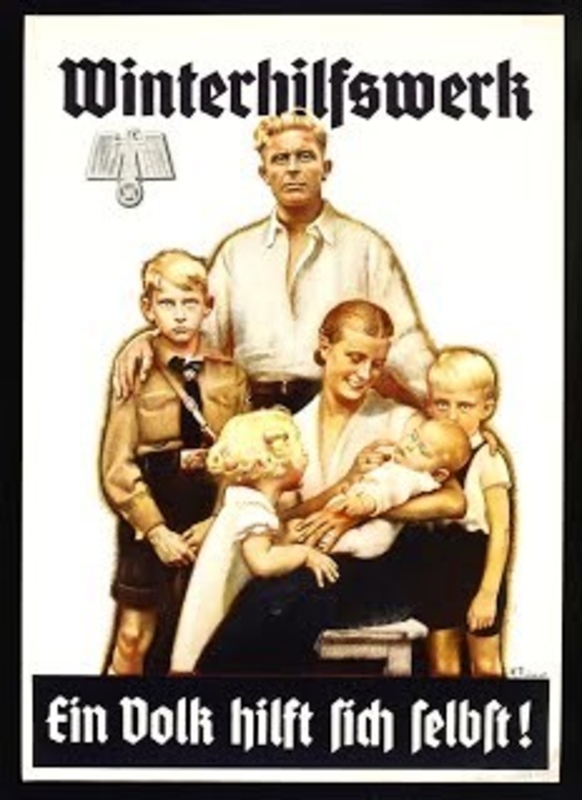

In Vienna, Truus Wijsmuller had an unpleasant exchange with a Winterhilfe (pronounced /Weentrr Heelfa/) “charity” worker. The annual donation drive, initially supporting poor people during the Great Depression, had secretly been turned into a warfare generation fund by the Nazis.

The Nazi propaganda machine presented the Winterhilfe as a social duty in countries all over Europe to support wholesome Aryan families, who had been treated badly during the Great War. Notice the swastikas on the jackets of the seemingly innocent, little girls.

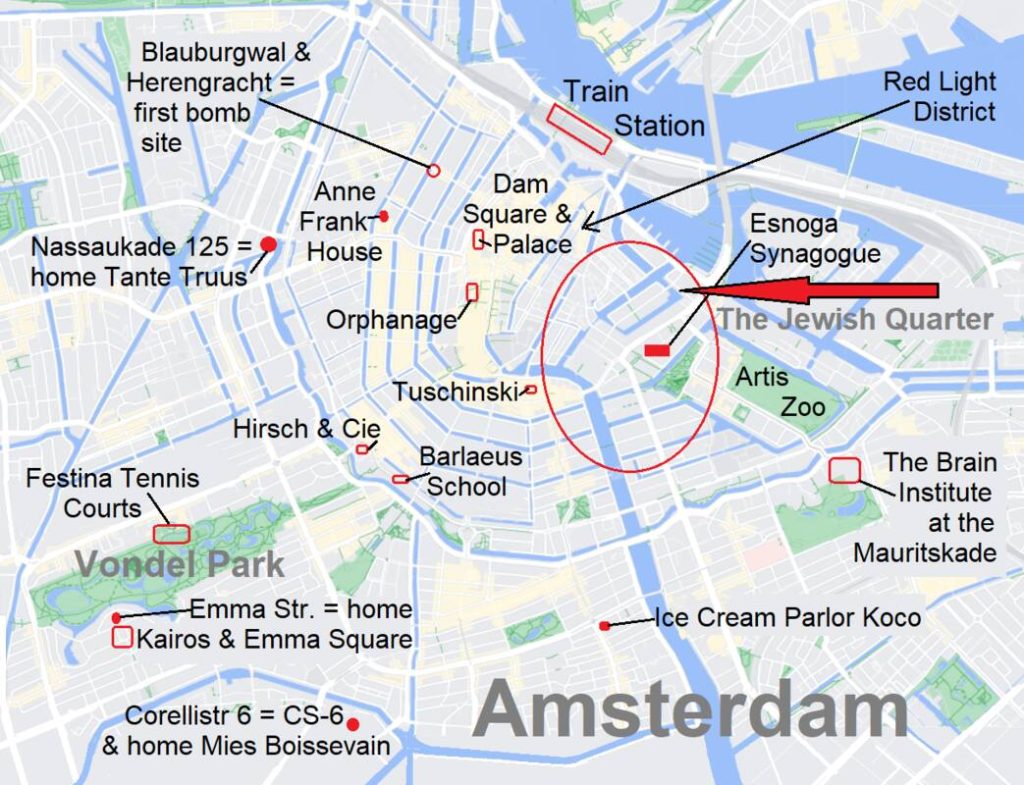

Truus Wijsmuller was not fooled by the Nazis and knew full well what they were capable of when she bravely traveled to Vienna to negotiate with the head of Emigration Services whose name she barely knew. It was less than a month after November 9th 1938, Kristallnacht (/Kree-stall-naghkt/). Despite this, it was a huge shock for her when coming from the romantic Schönbrunn Palace across the street, to see the bloody corpses of Jewish people in front of the gate of Palais Rothschild.

Unknown photographer

These Jewish people had been standing in line to get visas when Nazis decided to drive their trucks into the waiting masses. Instead of turning around in utter dread, she steeled herself, stepped over the dead bodies, and met with Adolf Eichmann because she had to save the children.

Unknown photographer

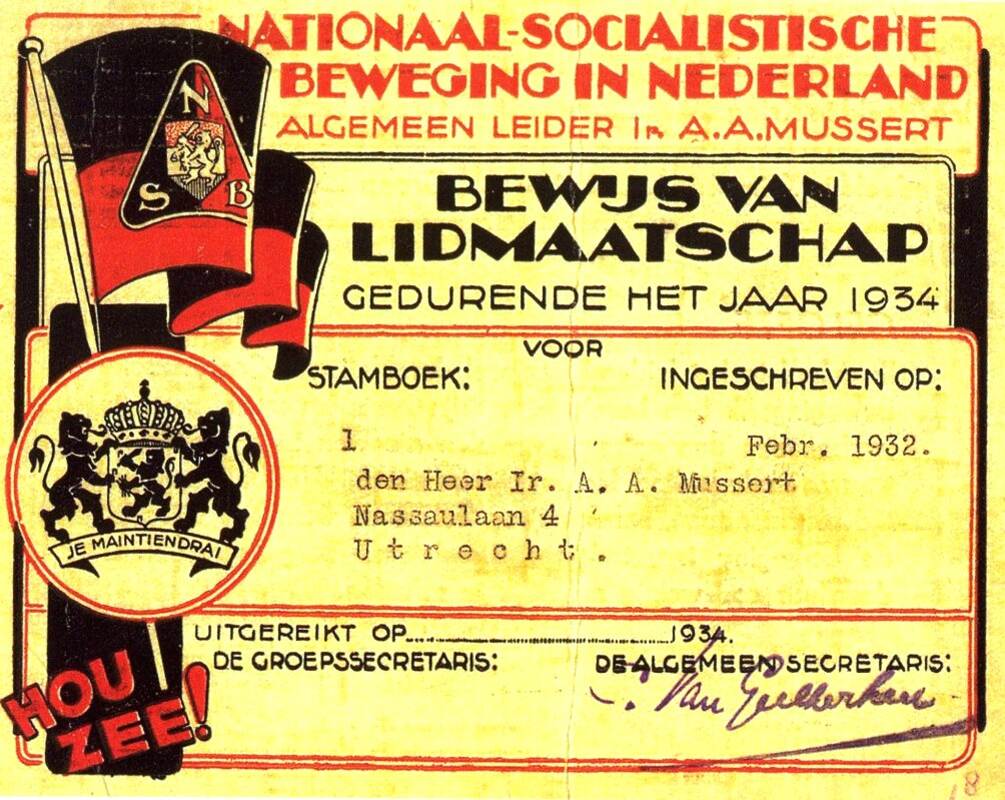

German-Austrian SS-Obersturmbannführer Otto Adolf Eichmann was one of the main architects of the Holocaust. As the head of the Nazi “Emigration Services” in Vienna, he had requisitioned Palais Rothschild where he received Truus Wijsmuller. After studying her physique and calling her “crazy,” he challenged her to arrange transportation for 600 Jewish children by the end of that week. He saw it as a joke and even promised her she could get another 9400 children if she succeeded, which he did not believe.

After the war, Eichmann hid in Argentina until he was tracked down by the Mossad and hanged for his crimes. Talking about Eichmann, Hannah Arendt coined the phrase “the banality of evil,” which other journalists and lawyers confirmed; he seemed “common,” yet completely devoid of feelings.

Fact or Fiction: Except for the brief scene in Schloss Burg of the young Adolf Eichmann with his mother, all the other details are factual. Notice that the antisemitic “Stab-in-the-Back myth” Eichmann referred to was a conspiracy theory Hitler promulgated, claiming Germany had not lost the First World War. In the 21st century, a similar “Stop-the-Steal myth” echoed the demagogue’s tactics.

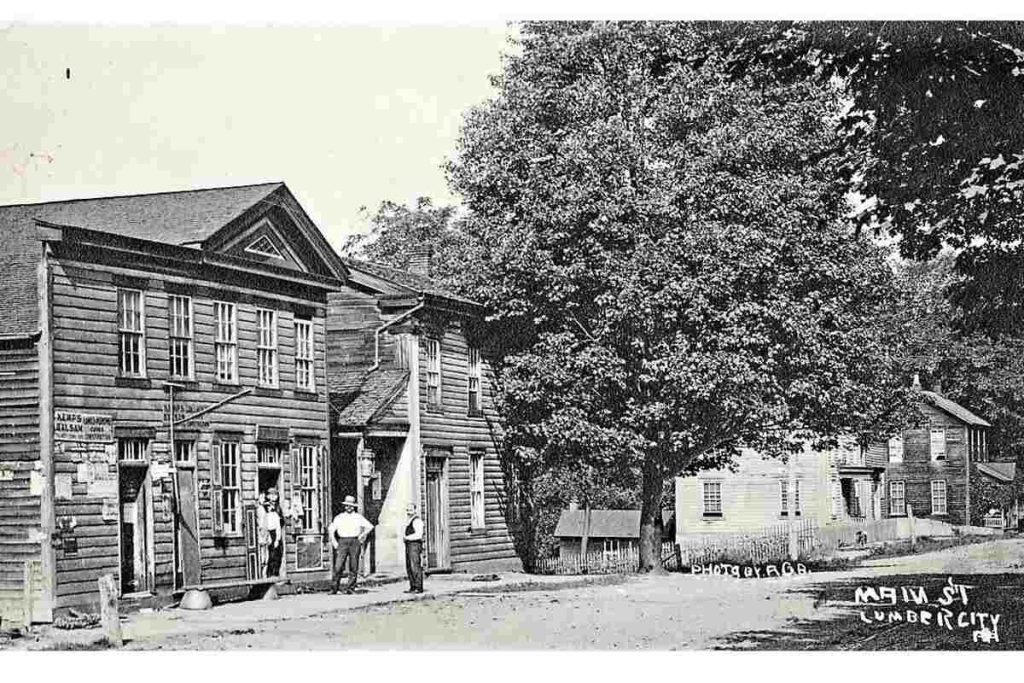

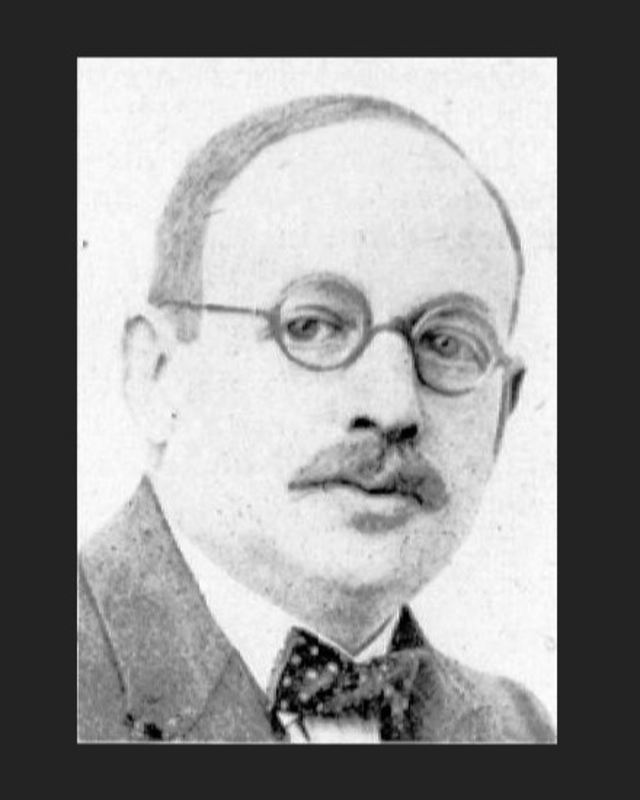

Unknown Photographer

Dr. Desider Dezsö Friedmann was an Czech attorney who lived in Vienna. He had become a representative of the Viennese Jews. He helped Truus Wijsmuller prepare the first Kindertransports. He survived the concentration camps of Dachau, Buchenwald, and Theresienstadt before his death in Auschwitz in 1944. His wife died as well, but his daughters, Ernestine and Edwig fulfilled their father’s dream of living in Israel.

Picture credit: Jorinde’s sister, Rose

Mrs. Wijsmuller took Dr. Friedmann to what she called “Hotel Neue Bristol,” which is now the Marriot Hotel Bristol, a very elegant hotel right across from the State Opera House. It was frequented by the likes of President Theodore Roosevelt, opera composer Giacomo Puccini, and soprano Nellie Melba.

The famous chocolate “Sachertorte” Mrs. Wijsmuller ordered in the Belvédère Salon of Hotel Bristol for her and Dr. Friedmann is a Viennese specialty.

Picture credit: Jorinde

similar galleries

discover

JOIN MY NEWSLETTER

To receive announcements about new blogs, images, essays, lectures, and novels, please sign up.