MIES BOISSEVAIN -After the War

Photographer unknown

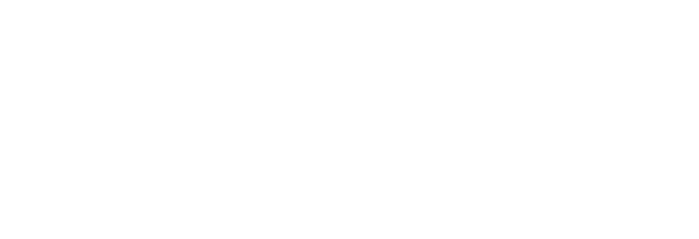

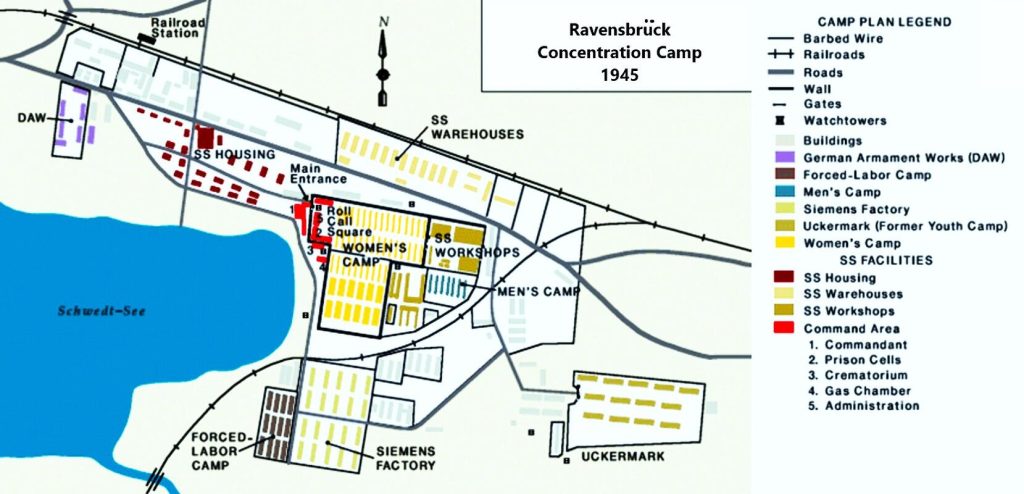

The hell of Ravensbrück cannot have been more different from the manicured lawns, the sunny atmosphere, and the clean serenity of this sanatorium in Halmstad, Sweden, where kind nurses and capable doctors took care of Mies Boissevain.

Photographer unknown

The Svenska Lottakåren was a Swedish Women’s Volunteer Organization to which about 5% of all the Swedish women belonged at the end of the war. Whether it was out of a sense of guilt for having remained neutral while the rest of Europe was burning, or whether it was out of altruism, these generous hostesses made a world of difference to the Dutch women who had come with the White Red Cross buses from Ravensbrück. Camp survivors relate in interviews how wonderful it was to be pampered by these kind and capable women.

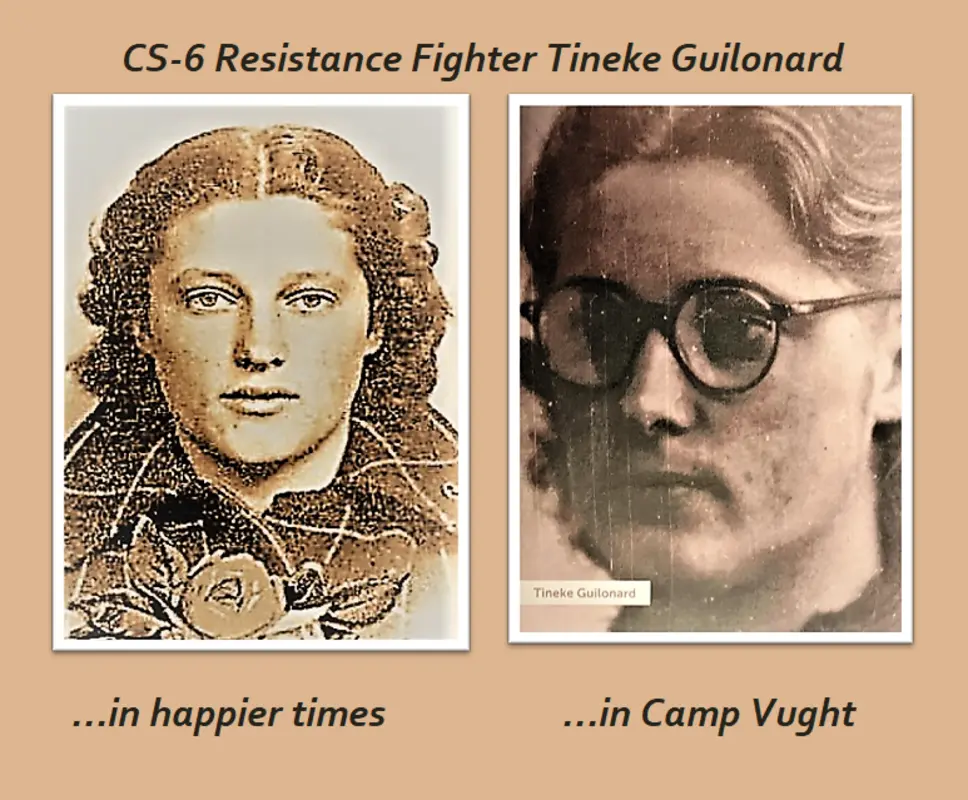

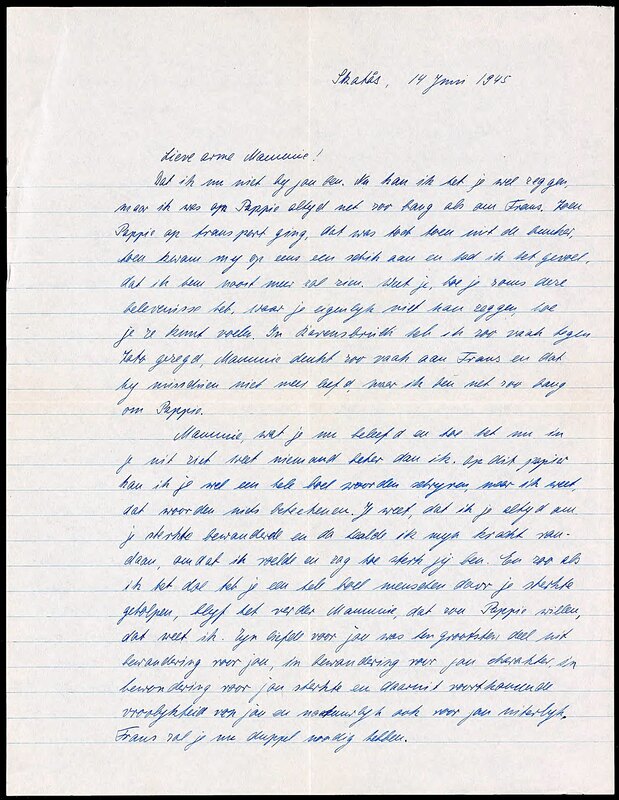

Fact or Fiction: Swedish volunteer Ulla, who takes care of Mies Boissevain, is fictitious. However, Father Fens was really the priest who told Mies that her husband had died. At the time, Mies weighed only 70 pounds, and having previously lost her sons G. and Janka, she was not coping well. This (real) letter from Evelyn Samuels from Skatås, Sweden to “Mammie Mies” in the Halmstad sanatorium is like a pep talk, encouraging her to remember how strong she is, and that her strength was what her husband admired the most in her as well:

Evelyn points out that “poor Mammie Mies’” strength is what not only earned her respect, but it is also what she inspired in others. The last words on the page remind Mies that her son Frans will now need her more than ever and that her husband would have wanted her to go on…

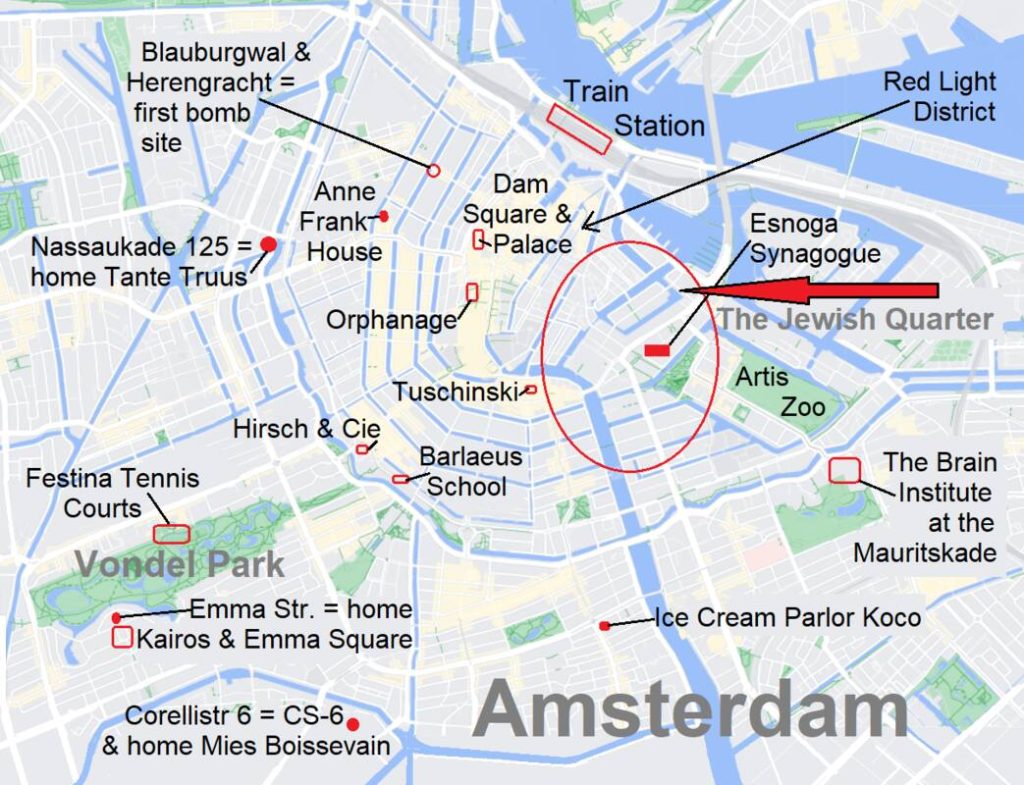

When Mies was finally allowed to return to Amsterdam to her daughters and Frans ( the only surviving son), their home in the Corelli Street had been taken over by someone else.

Photographers unknown, adapted by Jorinde

It must have been strange to go from the posh Emperor’s Canal House to the far more modest Corelli Street row house to an apartment in the Hondecouter Street within the span of five years.

Due to the lingering malnourishment and hatred caused by the war and the Hunger Winter in particular, no one in Amsterdam wanted to hear about the horrors of the camps. Because they had no other place to go, Mies lived with her daughter for a while as did former foster-child Theo Olof and his new wife.

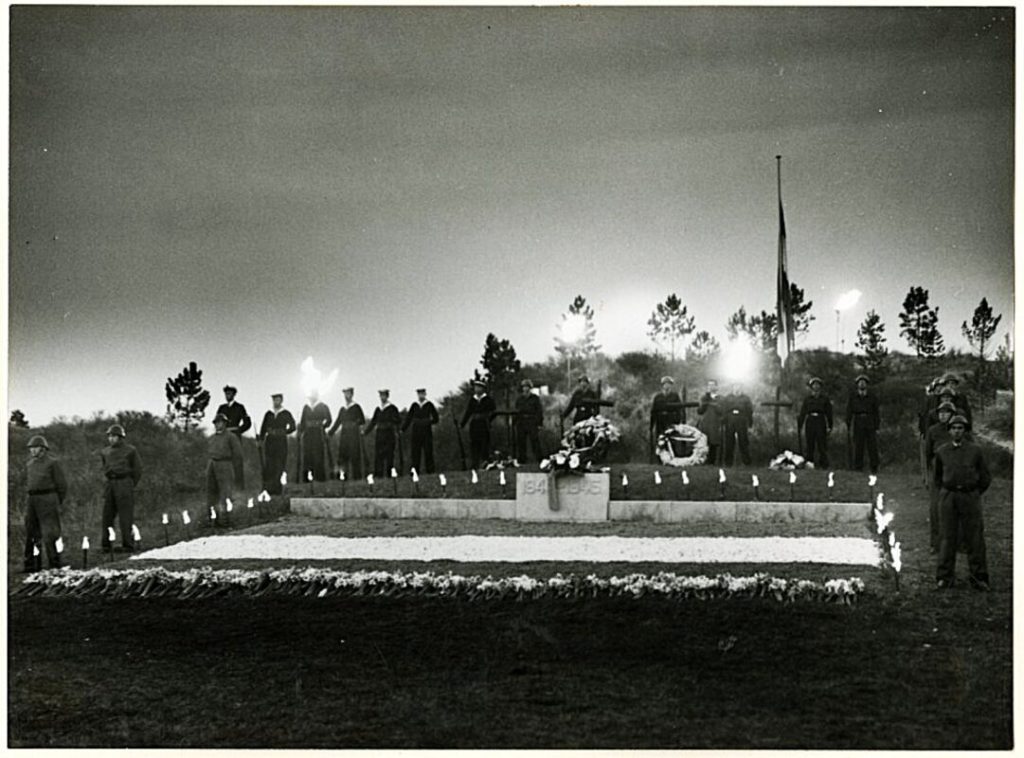

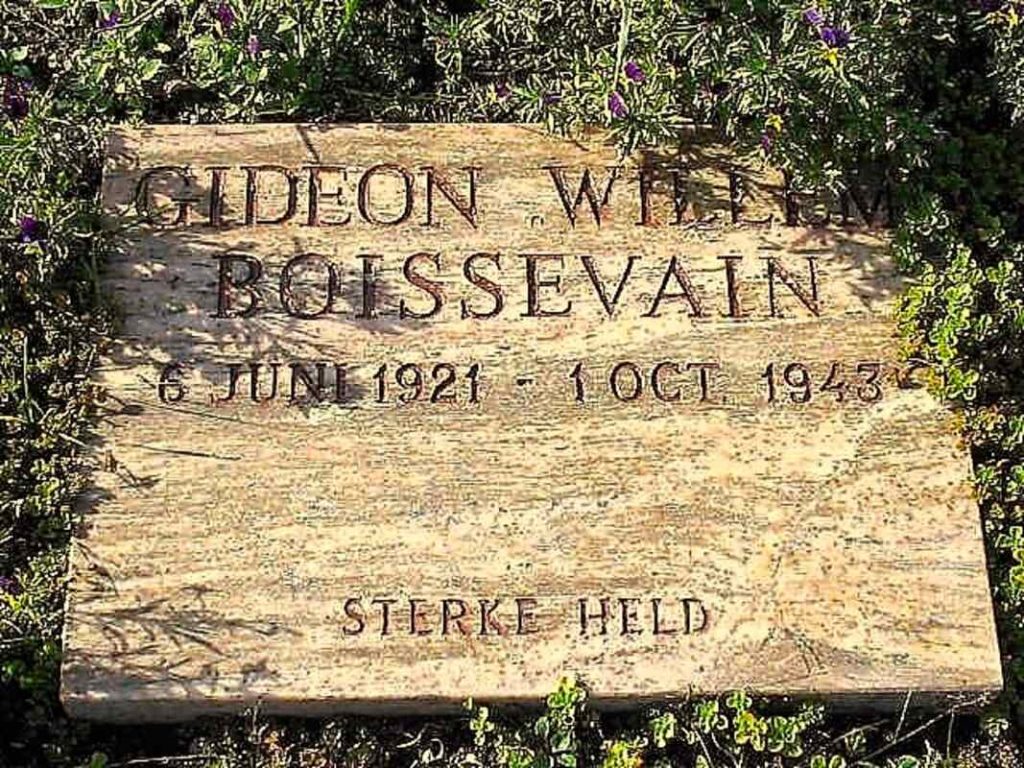

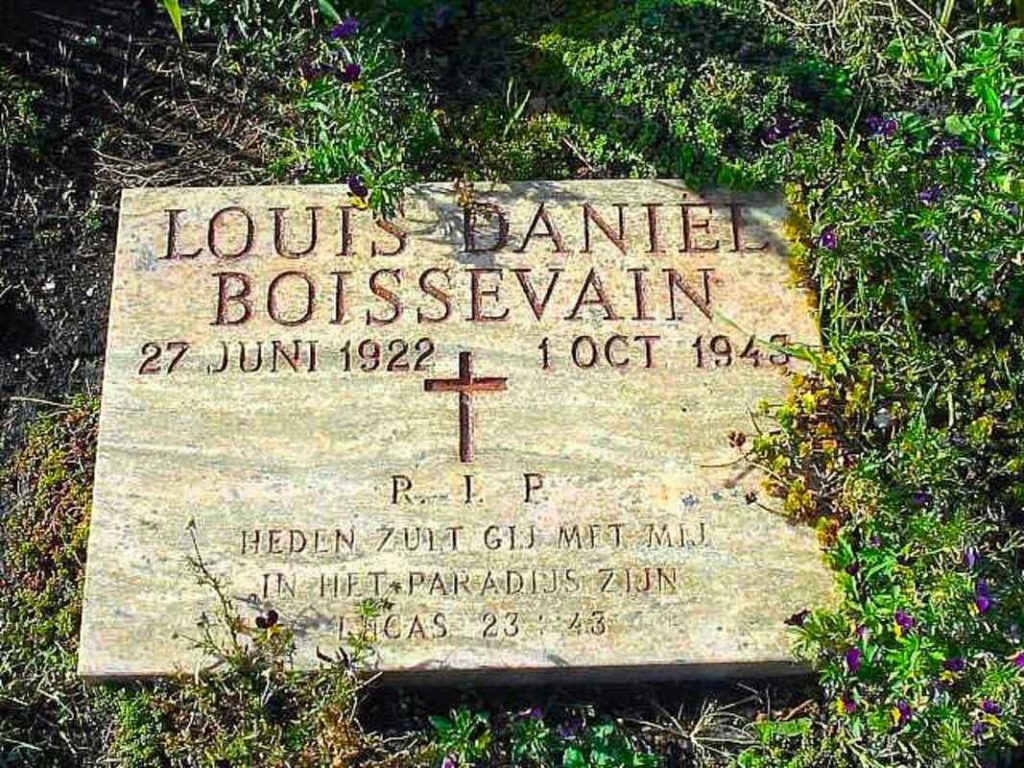

The graves of Mies’ two sons as well as her nephew are in the dunes of the Honorary Cemetery near the city of Bloemendaal (which is kind of like the Arlington cemetery of Holland).

* * * * *

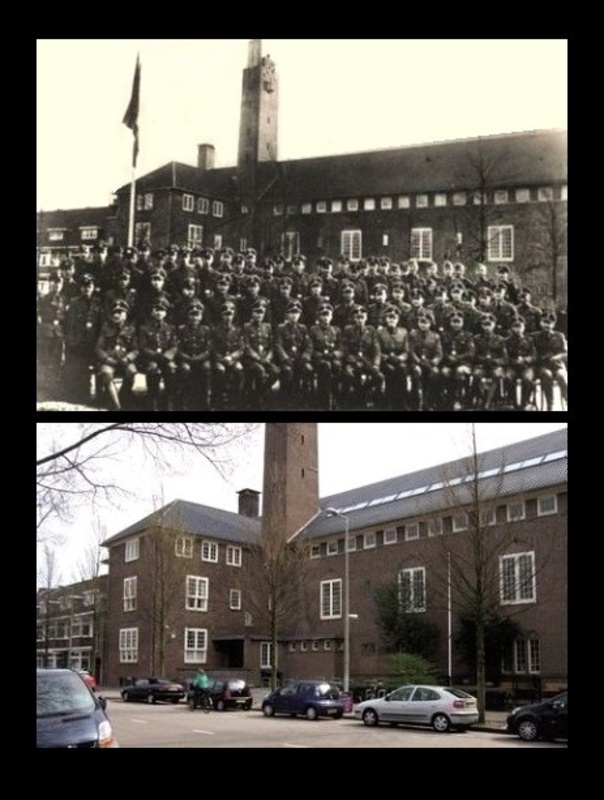

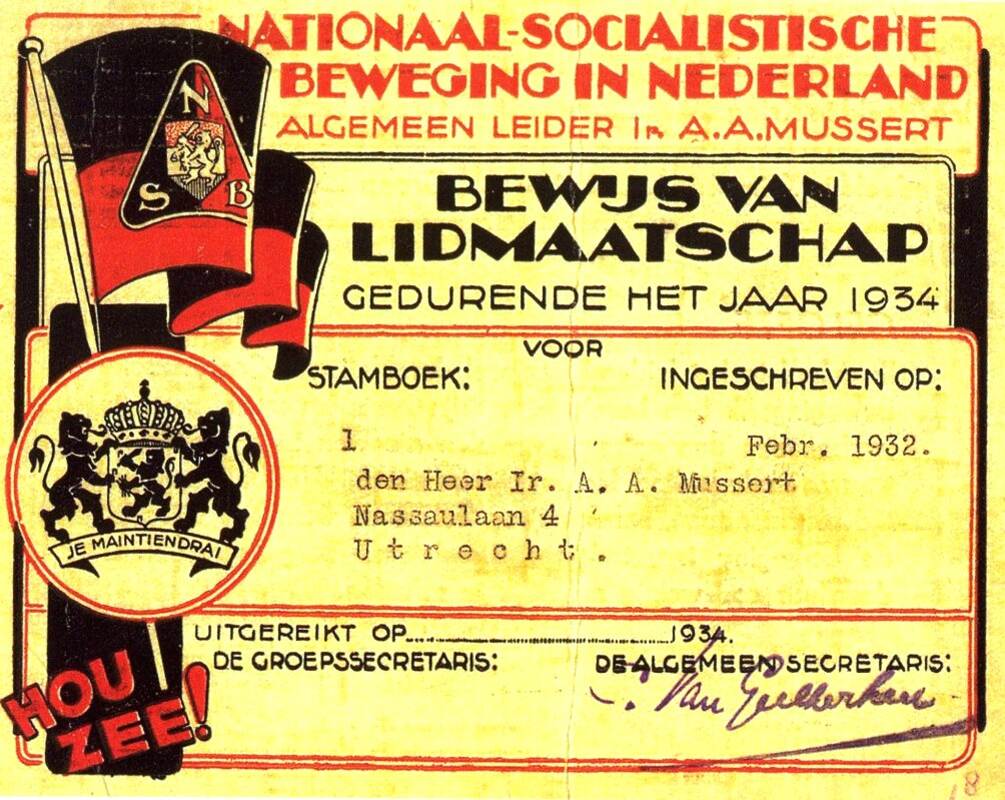

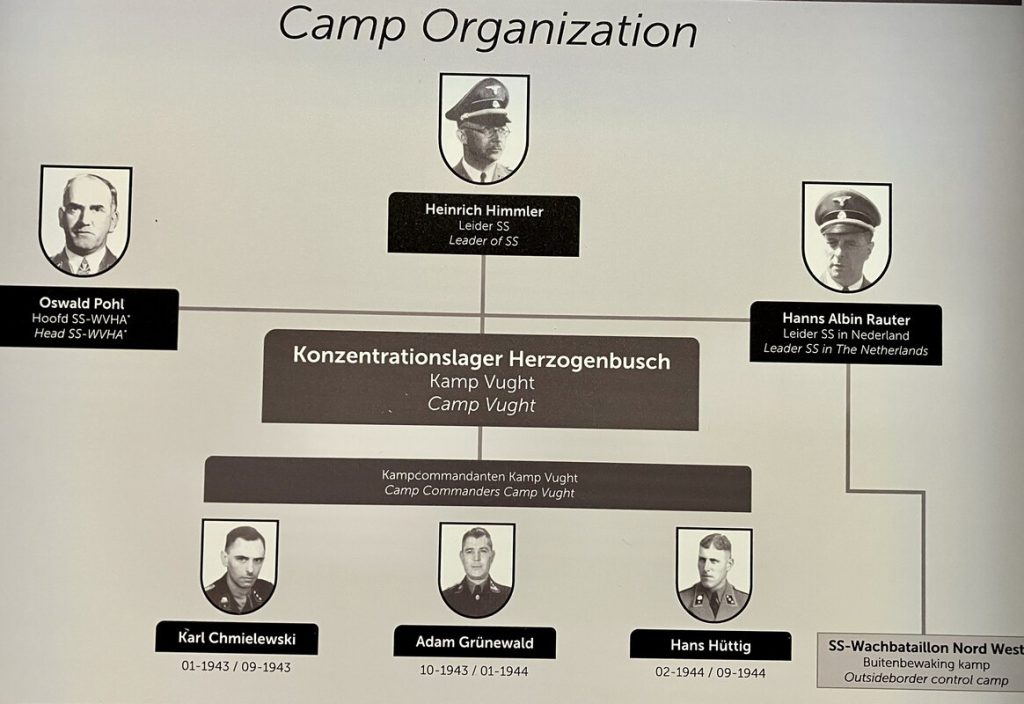

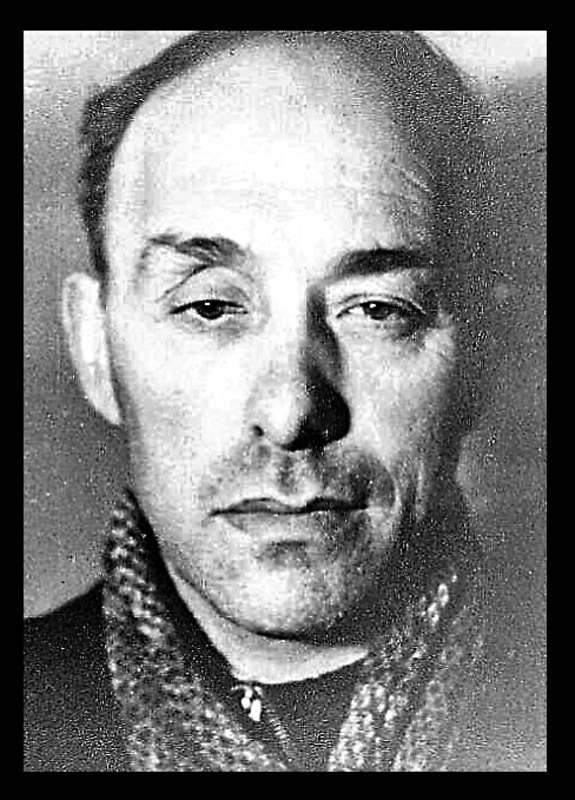

Facts -not Fiction: The person responsible for Janka and father Boissevain’s death as well for sending Mies, son Frans, and niece Thea to death camps was a man called W. C. Mollis. He was a Dutch police inspector and collaborated with the Sicherheitsdienst in Amsterdam. He beat his second wife and daughter and was a ruthless “Jew-hunter.” He helped put Truus Wijsmuller in jail and had been a part of the so-called Silbertanne Commando responsible for the executions of hundreds of Resistance fighters and doctors in particular.

Photographer unknown

After the war, when his war crimes were spelled out in court, Mollis merely said that he couldn’t help it because he was following orders. The attorney for the city of Amsterdam said in his closing argument that Mollis had committed any war crimes possible and that such a “cruel, lowly coward only deserve[d] one punishment, the death penalty,” which was applauded by the audience. He was one of the few war criminals for whom the death penalty in Holland, which at that time was already considered “barbaric,” was reinstated temporarily.

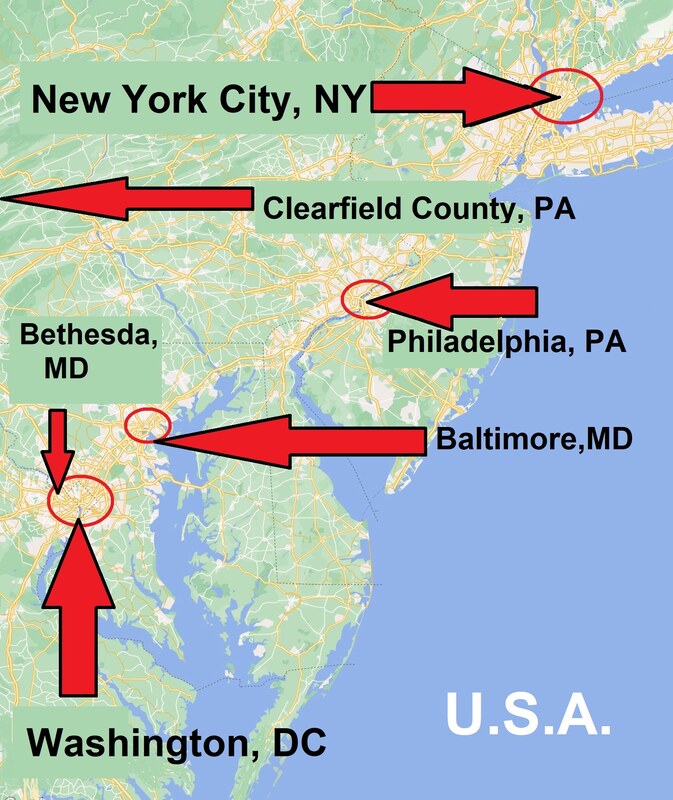

In 1947, while Mies Boissevain was promoting her “Skirt of Life” in the USA, her son Frans (who had survived Buchenwald) called her to tell her that on February 4th, Mollis was executed at Fort Bijlmer near Amsterdam (which is also where Maarten Kuiper, Anne Frank’s traitor received the death penalty).

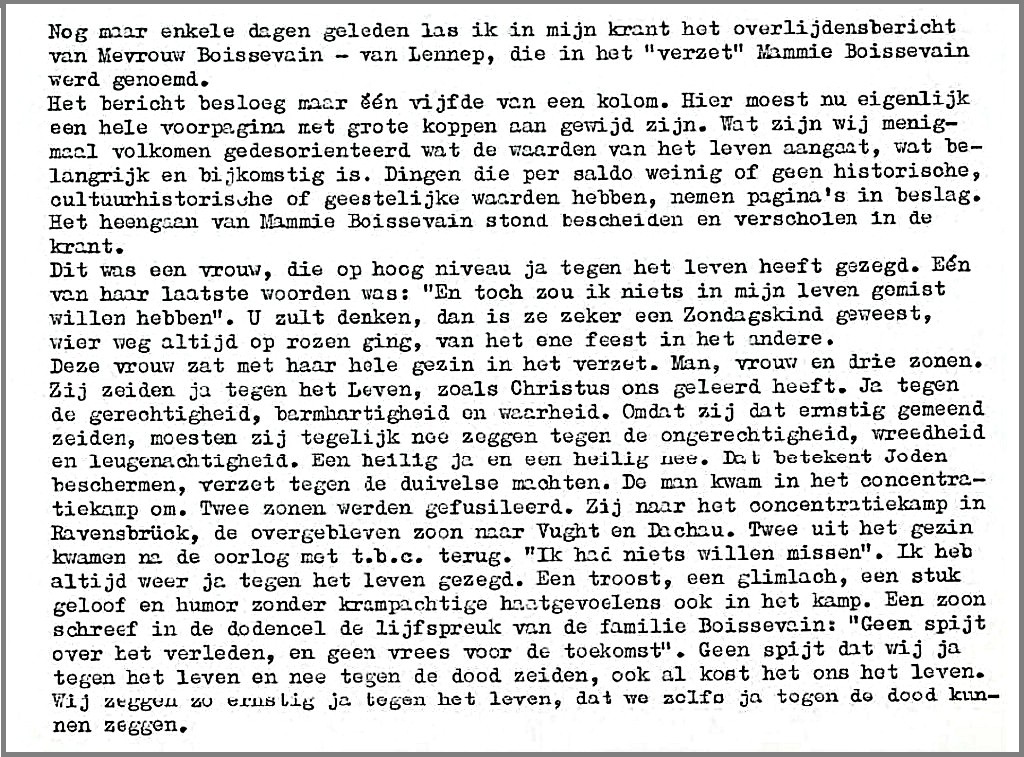

Mies Boissevain survived Mollis by 18 years; on February 18th, 1965 she passed away from cancer. The speech below (from her funeral) underscores that people like Mies are hardly noticed by society; she was relegated to less than a column in a newspaper with screaming headlines about unimportant things. In awe, the writer states that despite the hardships of Ravensbrück and of losing sixteen members during the war, Mies Boissevain still cheerfully said that she would not have wanted to” miss a single thing in [her] life.”

Unknown Writer

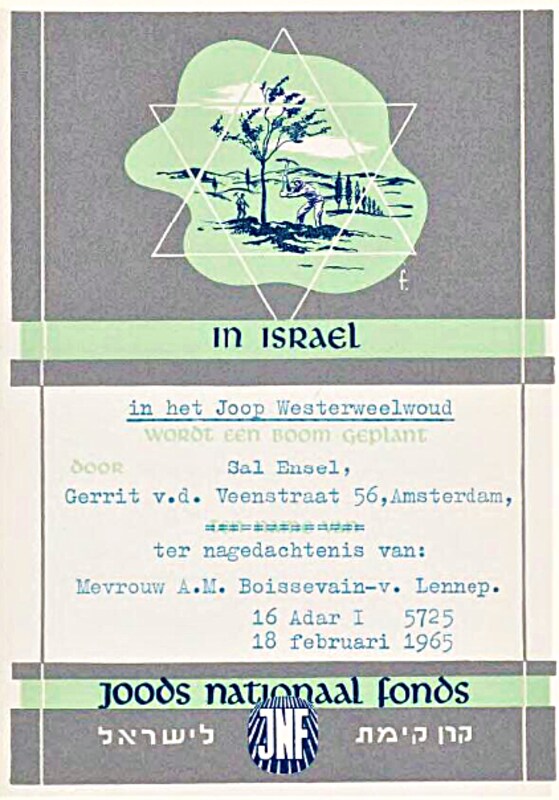

Mies was not seen as a Resistance hero. She was well-liked but had “only” been a mother and “Camp Mother” encouraging and taking young women under her wing in two Nazi camps. Just like Truus Wijsmuller, Mies never received any awards or recognition, yet a tree was planted in her honor in Israel.

similar galleries

discover

JOIN MY NEWSLETTER

To receive announcements about new blogs, images, essays, lectures, and novels, please sign up.