Women World War II Warriors

Under-Representation of Women World War II Warriors

by Jorinde (Maryland, USA on March 10, 2018)

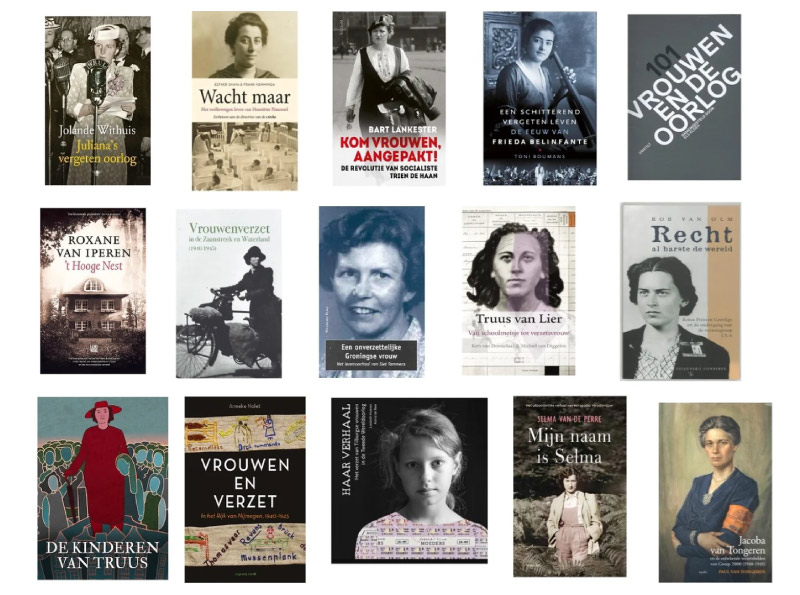

When asked about the most famous people associated with the Second World War and the Holocaust in particular, the average American might say, “Anne Frank and Oskar Schindler,” which are a female victim and a male savior. Even most Europeans might not know many Resistance fighters by name -Let alone female resistance fighters. The mostly male historians who wrote the history books right after the war, have by and large omitted those selfless women who hid Jews, printed ration cards and resistance pamphlets, and occasionally spied, sabotaged, and killed just like their male counterparts.

It was not until the eighties that female Resistance fighters like the Dutch Hannie Schaft (about whom the movie The Girl with the Red Hair was made), the American Virginia Hall (“the most dangerous Allied agent” according to the Nazis), and the German Sophie Scholl (of White Rose fame) became better known. And while Dutch Queen Wilhelmina was known to have a portrait of Helena Kuipers-Rietberg, aka “Auntie Riek,” in her palace, the driving force behind a national network for hiding Jews did not always get the credit she deserved.

Also, in my native country of the Netherlands, which is known for its alleged equity of men and women, it was not until a few years ago, that some citizens finally noticed that of the eighty or so Amsterdam street names in the New-West area commemorating Resistance Fighters not a single one was of a female Resistance fighter. There was and is a “Reina Prinsen-Geerlingssingel”…Not to take away from that fact that the lady was part of the militant resistance group CS-6 and was shot to death in Sachsenhausen, I cannot help but think that perhaps the fact her very well-off parents established a literary prize in her name after the war has something to do with that.

Regardless of the reason, the reality is that it took till 2016 for five bridges over the many canals in that area to be named after female resistance fighters; Bridge 600 is now called “De Frieda Belinfantebrug” to commemorate this Dutch-American cellist, conductor, and Resistance heroine, who had to don men’s clothes to escape the Nazis. Bridge 601 bears the name of the “Girl with the red hair,” Hannie Schaft, while bridge 603, 628, and 629 are named after Henriette Pimentel, Hester van Lennep, and Henriette Voûte respectively (who saved thousands of Jewish children.)

Professor Dr. Marjan Schwegman (of the NIOD / Netherlands Institute for War Documentation) rightly remarks in her essay about Paul and Jacoba van Tongeren (Aspekt, page 378) that men have routinely reduced the roles that women played during the war. She mentions among others, Esmée van Eeghen, co-leader of her own resistance group in the North-Western part of the Netherlands, who was reduced after the war to the rank of “courier” by a male fellow-resistance fighter and so-called historian.

Likewise, Maria Björg asks herself in the essay “Les femmes et la Résistance: une Histoire Oubliée (Women and the Resistance: A Forgotten History)” why it had to take till the turn of the century for films like The Story of Lucie Aubrac and Female Agents to be made. Like Professor Schwegman in the Netherlands, she sees the role of women and their place in French society at the time as the main reason why their work in the resistance has been under-documented.

Women were not mentioned in the history books as “Resistance Fighters” because the concept of a militant woman ran counter to the dominant culture of seeing women solely as mothers and caregivers. Yet it was precisely because women were not seen as being capable of being “warriors” that they were in fact highly successful in transporting ration cards in their pregnancy corsets, smuggling Jewish children via networks of nursery and elementary schools, and seducing Nazi officers to obtain counterintelligence.

While a woman during the 1940s was told by American propaganda posters “I can do it,” she was not allowed to remain Rosie the Riveter after the war was over and her husband wanted his job back. Similarly, British posters asked women to become nurses, but posters from both countries cautioned that “a slip of the lip, [could] sink a ship” and “keep mum, [because] she is not so dumb,” suggesting that women can work in factories and become able nurses, but should not be trusted with classified information.

Like Kathryn Atwood states in her book Women Heroes of World War II, “…there are other heroes in World War II, many whose names are not as familiar as those of U.S. generals Patton and Eisenhower but whose courageous actions helped win the war. These are the women heroes of World War II.” The question is not whether women were just as instrumental as men in winning the war; instead, we should ask ourselves if we can redefine the term “war hero” to include those who supported the war effort in the shadows or openly, but did not fit the stereotype of the male “warrior.”

Even if some of them “just” hid people or delivered messages or food, they risked deportation and death – Just like their male counterparts. Surely, those “Women Warriors of World War II” deserve a little more respect than they have been given the last 70 years? While almost all of them have passed away of natural causes by now, their children and grandchildren need to know so that they can teach the next generation never to forget, to stand up for what it right, and to honor their (grand) mothers appropriately.

MORE essays

discover

JOIN MY NEWSLETTER

To receive announcements about new blogs, images, essays, lectures, and novels, please sign up.