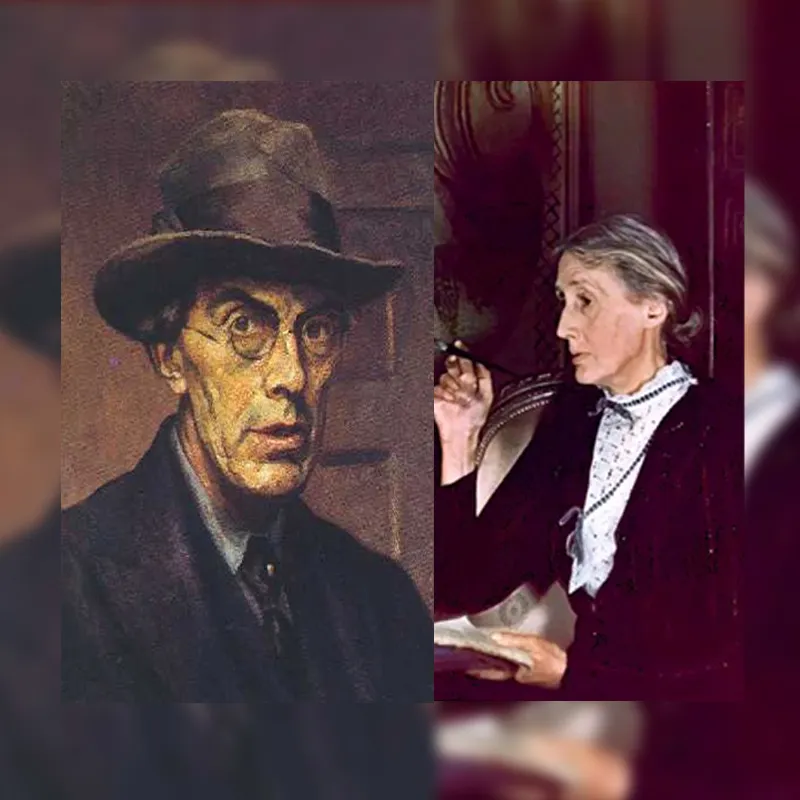

Virginia Woolf and Roger Fry

The Courage of a New Vision by Jorinde

Art Critic Roger Fry and Writer Virginia Stephen

Virginia Woolf was born in 1882 as the daughter of wealthy scholar editor Sir Leslie Stephen. Still in her early twenties, she started contributing to the Times Literary Supplement. When her father died in 1904, Woolf experienced the first in a series of many nervous breakdowns. Then she moved with her brother Adrian and her sister Vanessa to Bloomsbury, where the famous Bloomsbury group started. People like Lytton Stratchy, Maynard Keynes, Clive Bell, Duncan Grant, and Leonard Woolf would come together to discuss a renewal of the arts. Vanessa would marry Clive Bell and Virginia Leonard Woolf, while the former would openly have relationships with other men and the latter would flirt with men and women.

This is all common knowledge, as is the love and rivalry between the sister; Vanessa, the painter, and Virginia, the writer. A little after the beginning of the Bloomsbury group, however, the Bells met a man called Roger Fry in the train. He had interesting ideas about art and soon became a part of the group. He would also influence Virginia Woolf’s writing more than he has been given credit for. Careful reading of publications on Virginia Woolf by Hermione Lee and Panthea Reid as well as her own diary, letters, essays, and her biography of Roger Fry, suggest that Fry inspired Woolf’s vision of the novel. In turn, Woolf adapted this theory of the novel to suit her own purposes.

Roger Eliot Fry was born in 1866, almost twenty years before Virginia Stephen-Woolf. While from a very strict Quaker family, Fry was first and foremost a Victorian, who went to Cambridge to study science. Despite the odds, he gradually became interested in the Fine Arts and returned from Italy in 1891 as a painter. It was by then that he started doubting the truth and value of mere representation. He started writing long letters to his parents and friends debating what art should be.

In her biography of Fry, Virginia Woolf says that he was always completely open to any new idea or opinion, but would proceed to test it and sometimes go off in the opposite direction (86). He felt that change and renewal were essential for growth and life. As Fry was shifting his allegiance from mimetic to less representational paintings, Woolf herself felt so pressured by her sister and their painter friends, that in 1904 she considered giving up writing for painting (Reid 344). Instead, she kept working on the first version of a novel she then called Melymbrosia. Yet it was obvious that she was not sure of herself or her technique, so she would revise and rewrite it for years. Not long after Virginia Stephen met Roger Fry, she stated in a letter that she wanted to “re-form the novel” (Letters, 1:356), even though she did not quite know how to do it. The next year, in 1909, Roger Fry wrote “An Essay in Aesthetics” in which he discussed his views about the very techniques and aesthetics Virginia was ambivalent about. Although these may have been the first seeds that Roger Fry planted in Virginia Stephen’s fertile mind, she did not seem to take Fry’s words to heart yet.

Initially Woolf and Fry were not as close as in the years to come; first of all, he was yet another rival to her sister Vanessa’s affections when he started a relationship with her; secondly, he was a lot older than Virginia Woolf, who might even have been a little intimidated by him because by that time, he had become a well-connected and influential art critic, author, and curator of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

From a struggling painter and art lecturer, he had turned himself into an eminent authority in the world of the Fine Arts. He imbued his lectures with his passionate love for painting, inspiring his audiences with his enthusiasm. Bit by bit, he also started catching Virginia Stephen’s attention. He was more patient and personable than Virginia’s sister, his lover, Vanessa. Virginia would recall in her biography of him how “he would explain that it was quite easy to make the transition from Watts to Picasso; there was no break, only a continuation. They were only pushing things a little further” (164). What especially caught Virginia Woolf’s attention was that he also saw literature in the same way as painting. He remarked that “Cezanne and Picasso had shown the way; writers should fling representation to the winds and follow suit” (172). He challenged the writer in Virginia Woolf by scolding authors, asking her why “there [was] no English novelist who took his art seriously? Why were they all engrossed in childish problems of photographic representation?” (164). As if to enforce his opinions, Roger Fry would go out on a limb by organizing a controversial Post-Impressionist exhibition.

The official name of the exhibition was “Manet and the Post-Impressionists,” which ran from November the eighth, 1910 to January the fifteenth, 1911 at the Grafton Galleries in London. This was the first time that modern paintings by European artists like Manet, Matisse, Picasso, Cezanne, Gauguin, and Van Gogh had been brought together in one big exhibition in England. The name of “Post-Impressionism” was made up for a journalist, who wanted a convenient label. The exhibition was visited by a minimum of four hundred people daily, who were either excited by the new wave of modern art or like the majority, extremely shocked by what Roger Fry called a “revolt against the photographic vision of the nineteenth century” (Reid 116). He didn’t want imitations of life but an equivalent for life, shown by the structure, unity or texture of a work of art. However, visitors complained in the visitor-book that the show was “pornographic” and “stupid,” people sent angry letters and drawings made by their children to Roger Fry, and Dr. Hyslop and Professor Tonks declared the exhibition the work of madmen (Biography 156). Roger Fry was not even enraged or sad, but simply regarded these reactions as “philistinism” that needed to be opposed (Biography 157).

It was not just the exhibition that caused an upheaval that year. England in general seemed to be in turmoil, for the year 1910 was politically unstable too. First of all, Edward VII had died on May sixth 1910 and George V would not be crowned till the twenty-second of June 1911. Secondly, during that same period of time the Suffragettes, for whom Woolf did secretarial jobs, became more confrontational in their actions. And last but not least, ironically the exhibition had its press view on Saturday, November fifth, otherwise known as Guy Fawkes day, which was usually associated with fireworks and explosions (Stansky 207). While that week the exhibition officially opened, Asquith requested the dissolution of Parliament and wanted to have a public vote on the Lord’s veto. All party conferences did not remedy the situation, and the Liberal government was forced to call a second election in the same year.

The Status Quo had been challenged artistically as well as politically. Virginia Stephen wrote in an essay that “human nature changed” in December 1910, and that “all human relations” had shifted and with that changed “religion, conduct, politics, and literature” (Essays 1:320). But instead of directly referring to the exhibition, she discussed the influence of Samuel Butler and Bernard Shaw and the difference between on the one hand the more traditional writers like Wells, Bennett, and Galsworthy, and on the other hand, the more modern Forster, Lawrence, Strachey, and Joyce.

The fact that she pinpoints a transition in the history of English novel-writing at the date of the Post-Impressionist exhibition suggests that she saw a parallel between or even an intertwining of the arts of painting and writing. Virginia Stephen-Woolf’s position was actually very comparable to Roger Fry’s during the time of the exhibition; both had to cope with hostilities and outrage against the causes most dear to them. She was seen as a “crazy” Suffragette often suffering mental breakdowns, while he was being called “crazy” for bringing the “scandalous” Post-Impressionist exhibition to England and his painter wife had gone crazy, spending her last days in an insane asylum. Apart from their linking fates, there might have been another factor that threw them together. It is likely that the excitement of the young British painters who were inspired by Fry’s exhibition to renew English painting and join the growing international movement of modern art, rubbed off on Virginia, who was always surrounded by them. Especially when she saw that her sister Vanessa, whose constant affection she craved, became one of Roger Fry’s advocates.

Interestingly, Woolf was not only inspired by Fry and his art, but the cross-fertilization worked the other way as well, for the versatile Roger Fry had always had an interest in literature. In his early articles on art, Fry often used literary terms and referred to Blake or Shakespeare. He felt that the English were “incurably literary” and “liked the associations of things not things in themselves” (Biography 164). He preferred reading French books and envisaged for British literature the same abandonment of mimesis as painting had already shown itself capable of and wanted the novelists to follow Cezanne and Picasso’s lead. When some literary friends, like Arnold Bennett or Henry James would come visit Roger Fry during the second Post-Impressionist exhibition in 1912 to discuss their hesitations about the Post-Impressionists, Fry would convince them that “Cezanne and Flaubert were, in a manner of speaking, after the same thing” (Biography 183). At his exhibitions, he tried more and more to include the other arts and invited some French poets. In 1913, Roger Fry also explained in a letter to his friend Goldie Lowes Dickinson that he had been “attacking poetry to understand painting” because he felt that “the sense of poetry” was “analogues to the things represented in painting.” He concluded that the content of literature or painting were “merely directive form” and that the aesthetic quality was “pure form” (Biography 183). Later on, together with Charles Mauron, Fry tried to translate the French poetry of Stéphane Mallarmé into English .

Virginia Woolf wrote in her biography of Roger Fry that the arts of “painting and writing lay close together, and Roger Fry was always making raids across the boundaries” ( 240). As may be suspected from the wording of this statement, Woolf was rather possessive of “her” art, literature. And although she was immensely inspired by the visual arts, she only wanted to focus on writing. Likewise, despite all his statements and his interest in literature, Fry still favored a separation of the disciplines. Or as Woolf herself would say during her opening address to the Roger Fry Memorial Exhibition at the Bristol Museum and Art Gallery (on July 12, 1935): ” He wanted art to be art; literature to be literature.” In her biography, Woolf even had Fry proclaim himself ignorant on writing, yet critical of British writers, whom he saw as “mere illustrators.” Between the lines of Fry’s disparaging comments that literature might not be an art and that writers lacked conscience and objectivity, his intention to provoke what he felt was lacking in writers and in Virginia Woolf’s writing in particular are evident. She defended herself and her fellow writers by pointing out Fry’s deficiencies as a critic of literature. However, at the same time, she acknowledged that it was maybe because he was not a writer that his theories revealed “unexpected patterns.” She acknowledged that “Many of his theories held good for both arts” (Biography 240). There were design, rhythm and texture in paintings as well as in novels, which Woolf observed in the way Fry “would hold up a book to the light as if it were a picture” to show where “it fell short” (Biography 240).

Virginia Stephen develops into Virginia Woolf

As for Virginia Stephen herself, she gradually started developing her own theory of the novel. Through the essays and reviews she wrote as well as her own diary and letters, a pattern of her aesthetics of the novel developed. In “The Art of Fiction” for example, she summons English critics as well as novelists to be less “domestic” and “bolder.” She wanted them to leave “the tea-table” and abandon their convenient, but silly “formulas.” This could entail that “the plot might crumble” and that “ruin might seize upon the characters.” She concluded sarcastically that “the novel, in short, might become a work of art” (Essays 2:55). Paradoxically, as Woolf seemed to advocate a more or less plotless, dehumanized, or abstract kind of novel, she also believed that a book was not just a form to be seen, but an emotion to feel.

Just like Roger Fry said in Vision and Design that “significant form” is “the direct outcome of an apprehension of some emotion of actual life” (14), so Virginia Woolf aimed for a specific overall feeling in her writings. Where Fry wanted to replace photographic representation with spaces, color and texture, Woolf wanted to abandon the straightjacket of a (chrono)logical plot in favor of certain combinations of words, their connotative associations, the feelings they produced. Thus, both believed that “form,” be it a mimetic plot or picture, should be replaced by “significant form.” Form and content, vision and expression -or as Fry said “vision and design”- should be a perfect blend. Instead of traditional means to achieve “significant form,” anything might be used to achieve the overall feeling aimed for. In “Modern Fiction” Woolf states her objections against linear time, space, and plot sequence constructions, famously claiming that “Life is not a series of gig lamps…but a luminous halo” (Essays 2:107). She did not mean that there should be no form; instead, she meant that the form should be “under” the overall vision, supporting it, and making it meaningful.

Therefore, Virginia Woolf abandoned writing “superficial” mimetic plots and instead tried to “tunnel” her way into her writings. She started studying painter Paul Cezanne, who had expressed a similar feeling stating that “nature is more depth than surface” and that “the colors rise up from the roots of the world” (Kapur 15). Then she revised and rewrote her entire first novel again, using painterly jargon in her diary to describe her efforts: “One works with a wet brush over the whole, and joins parts separately composed and gone dry” (Diary 2:322). After Woolf discussed aesthetics and literature with Fry during a trip to Turkey in April of 1911, she tried to make the draft of her novel Melymbrosia less “literary” and more visual. She incorporated some of Roger Fry’s interest in primitive art in her book, talking about “new forms of beauty……primitive carvings colored bright greens and blues” (103) that replaced “the enormous accumulations of carved stone, stained glass and rich brown paintings which they offered to the tourist” (102). Woolf also viewed language and indeed the world around her now as “vast blocks of matter,” while people were “nothing but patches of light” (358). The stability that Leonard Woolf provided after he married Virginia Stephen in 1912, finally provided her with enough confidence to complete her first novel. By 1915, it was known as The Voyage Out, and Roger Fry considered it a work of genius.

Although Vanessa Bell had ended her relationship with Roger Fry, her sister Virginia Woolf would still see him quite often and remain true to his teachings. In July of 1917, Woolf wrote a review of a collection of essays by Arnold Bennett echoing his as well as Roger Fry’s question: “Is it not possible that some writer will come along and do in words what these men [the Postimpressionists] have done in paint?” (Woolf 319). In October 1917, Woolf had another conversation about aesthetics and writing with Roger Fry, who asked her if she founded her writing upon “texture or upon structure.” Although she was not quite sure what the “right” answer was, she said “texture” reiterating that she connected plot and structure (Diary 1:75). The year 1918 proved Fry’s influence on Woolf only increased, judging her nearly weekly reviews for the Times Literary Supplement. In the meantime, Woolf kept writing novels as well as shorter pieces, such as the very visual “Kew Gardens” (1919), which is another example of how painterly she had become. The light that reveals the people and the flowers at Kew Gardens and the water droplets under these flowers are described in a non-conventional way, linking their imagery. The light almost becomes liquid as it stains, expands, and settles on the flowers before it “flash[es] into the air above” (84). The light also links the people passing by the flowers to the flowers by suggesting that they flutter by them like butterflies. In addition, the perspective from which the scenery is described often recalls an Impressionist or at times an abstract painting. From the perspective of the snail for instance, a flower is so gigantic that it takes on abstract qualities; the opening cup of a flower is reduced to a “yellow gloom” with a “straight bar, rough with gold dust” sticking out of it (84). From the perspective of the author or a viewer, however, we see the light spreading into what seem for the snail “vast green spaces” (84). Woolf’s masterful story was followed in 1920 by Roger Fry’s equally successful Vision and Design. This was the first book of modern art criticism after the Post-Impressionist exhibition.

Mrs. Dalloway, a “Refractionary” Novel with a “Masterful” Design

Towards the end of 1923, Woolf was writing Mrs. Dalloway, and she noted in her diary that this was the most “refractionary” (Diary 2:262) book with a “masterful” design that would unite it (Diary 2:272). During those days, she also mentioned in her diary that there were no writers to match what Picasso did in paint (Diary 2:264), perhaps implying that she thought of doing so. In a way, Woolf did match Picasso’s Cubist compositions in Mrs. Dalloway. Pablo Picasso’s Cubist paintings show that the so-called “negative” spaces between the objects or subjects are just as important as the “positive” spaces of the objects or subjects themselves. In fact, Picasso often seems to place the negative over or next to the photographic image, abandoning mimetic representation as known to Western man since the Renaissance. This raises “significant form” -as Roger Fry would call it- over traditionally “realistic” representation. As long as the colors, texture, and composition communicate certain life-like or “real life-related” emotions, it does not matter that a woman’s body looks like a folded-up box or that her ear is on her forehead. Virginia Woolf juxtaposed Septimus Smith’s “negative space” with Clarissa Dalloway’s “positive space.” They never meet. Their spaces are distinct, yet they edge each other’s consciousness as well as “border” on each other in the painterly sense; “But that young man had killed himself. Somehow it was her disaster-her disgrace” (282). Even though Mrs. Dalloway’s story -the main plot- fills most of the canvas and Septimus’ story -the subplot- only fills up the gaps left over; they comprise the picture together.

For if Cubist paintings show objects from many different angles at the same time, her novel also consists of many fragments and viewpoints. Virginia Woolf weaved an extensive web of heterogeneous viewpoints; the entire novel is about the way people see things. In step with the Cubists, Peter Walsh thinks that he has the ability to “see around things” (159). Yet ironically Clarissa Dalloway wants him to risk his “one little point of view” (168). For although Peter sees himself as an “adventurer… careless of all [the]damned proprieties” of the British Empire, he is very much a part of it and “landed…last night from India” (80). Mrs. Dalloway herself has no illusions about her “split” personality and “dualistic” view of the world. She fully realizes and accepts that she is a part of the British Empire by inviting the Prime Minister to her party, yet on the other hand, she also has a private, hidden inner freedom that is “invisible; unseen; unknown” (13). This side of her personality allows her to view the world around her as one of her own parties; the parks, the omnibuses, stores, and streets become places to celebrate life. In such places in London, people from all walks of society are present – From the deranged old hag at the Underground to the upper classes of Lady Bruton and the Prime Minister. Woolf uses several devices within the novel to ensure clarity and unity. As the title suggests, Mrs. Dalloway provides the focus of the novel. She is the center of all the perspectives and the novel starts and ends with her. She also represents the Golden Mean of all the other perspectives. Despite the fact that she is the hub, Woolf uses a peculiar “democratic” style. The non-authoritarian omniscient narrator seems to slip in and out of people’s minds, creating a continuously shifting perspective. She often uses an undetermined passive voice or words like “one” or “people” that enable the reader to identify easily with narrator as well as the person speaking -As if we are all Virginia Woolf, Clarissa Dalloway, Sally Seton, or Peter Walsh.

All the separate strands of the plot come together by people meeting each other and visually or symbolically through certain sounds or bird-, flower- and tree-imagery. Woolf took her “wet brush” to “join things separately composed and gone dry”. Mrs. Dalloway sees and hears the car of the Prime Minister, who is later noticed by the narrator when everybody is in the park. The Prime Minister will later visit Mrs. Dalloway’s party too. Then there is the airplane that writes in the sky, prompting most of the major protagonists to interpret the illegible writing in their own way. Peter Walsh and Rezia Warren Smith meet each other without knowing it in the park. Everybody constantly tells time or notices the strokes of the Big Ben. Peter Walsh ironically calls the siren of the ambulance that speeds to collect Septimus’ horribly mangled body “one of the triumphs of civilization” (229) without realizing either the failure of civilization in this case or the fact that he has seen Septimus previously in the park. To complete the circle, it is Sir William Bradshaw, who tells Clarissa about Septimus’ death at the party.

The variety of points of view included for the first time in history the truly feminine point of view of the narrator. Maybe the very non-authoritarian omniscient narrator should be considered feminine to begin with because of its -pardon “her”- willingness to allow for other points of view. Even though this so-called female quality had been incorporated in painting by Roger Fry and the mostly male Cubists, they typically wanted everybody to accept their multiple views. The difference between them and Virginia Woolf consists in the fact that her overall vision in Mrs. Dalloway is distinctly female. The narrator and the main character are not only female, but they also see life as having female characteristics. The dusk in London is compared to a woman “who had slipped off her print dress and white apron to array herself in blue and pearls” and like a woman “tumbling petticoats on the floor” the day “shed dust, heat, colour” (245).

It is precisely at this point, that Peter Walsh feels a “shift in the whole pyramidical accumulation which in his youth had seemed immovable” and he notices that it “had pressed, weighed them down, the women especially, like those flowers Clarissa’s Aunt Helena used to press between sheets of grey blotting-paper.” He realizes that “she was dead now” and that she “belonged to a different age” (246). Peter, who thought that he “could see around things,” just returned from India and fails to see that he is part of the very white, male-dominated British Empire. The evils of that society are personified by Sir and Lady Bradshaw who care about nothing but “proportion” and try to purge England of people who don’t fit into their composition. Lady Bradshaw literally takes perfect pictures of England of rolling lawns, well-kept estates with flawless models of people, while her husband, who is a doctor, manipulates people, forbids certain undesirables to have children and locks up people of whom he does not approve in mental institutions. The narrator points out to the reader that this excessive love of proportion perverts humanity and spreads like a disease to places like India or Africa. It can suck the life out of entire cultures like a vampire, feasting on the blood of others. In the heart of the British Empire itself, London “merely” keeps women in their place. Even though Clarissa Dalloway is clearly the main person of the novel bearing her name, her story ends with Peter Walsh’s vision of her. He literally puts her in his sentence. He sentences her in a sense to being what he wants or needs her to be: “For there she was.”

To the Lighthouse ~ Framing Reality

Virginia Woolf’s next novel, To the Lighthouse, was published by her and her husband’s own Hogarth Press two years later in 1927. It unites many of the aesthetic questions that Roger Fry had been discussing with Woolf since 1910. Moreover, there are some indirect references to him in the book too: one of the Ramsay children is called Roger and the boeuf en daube that unites all the visions of the dinner guests was Roger’s specialty. Woolf actually said to Fry that she would have dedicated To the Lighthouse to him if she had thought it good enough (Lee 284). She wrote to him on the twenty-seventh of May 1927: “What I meant was (but would not have said it in print) that besides all your surpassing private virtues, you have I think kept me on the right path, so far as writing goes, more than anyone – if the right path it is” (Letters 3:385). And although Lily Briscoe’s ideas about art were very similar to Vanessa Bell’s, Roger Fry had at least partly shaped them in both Vanessa as well as Virginia.

To the Lighthouse starts with Mrs. Ramsay saying that the weather will be fine, while her husband immediately contradicts it. This indicates that the union of the parents is based on their totally different views. Their point of view depends on the kind of frame it is surrounded by. One of the most important devises Woolf uses to expose these frames or the way we form pictures or perspectives, is by paralleling the main action in the novel of Mr. Ramsay and his children reaching the lighthouse with the creation of a painting of the by then deceased Mrs. Ramsay by Lily Briscoe. In doing so, Virginia Woolf clearly distinguishes between the action of the plot of the novel, the action of creating the painting, and the painting itself. The framework of this triple perspective counters the Edwardian realist’s conviction that his truth is the only truth. Woolf shows that she realizes how limited her truth was among the many other truths possible. Via Minta Doyle’s song “Damn your Eyes” (82), Woolf might have been condemning the single, realist vision of what can only be observed literally on the surface. Instead, she opted for multiple perspectives and glides from one person’s thoughts to the next. In addition, Woolf exposes traditional social and aesthetic frames by framing them, and so “disarm[s]” them, showing life in all its complexity (Handley 17).

One of the ways in which Virginia Woolf makes this technique visual is through symbolic images that are often connected with water. In her novels and diaries, Virginia Woolf often refers to intangible abstractions in life, such as “the soul” or “love” or “the truth,” as things hidden under the surface of the ocean (Diary 3:112), much in the same way the structure or “design” of a novel is hidden under the surface. In the novel, Mrs. Ramsay is described as a fountain watering her husband’s dry earth, which makes her sometimes feel like a mere “sponge sopped full of human emotions” (39). When she wants to forget about all the other people that drain her, she identifies herself with the dark ocean under the wedged-shaped beam of light of the lighthouse. When she sits on the steps of their summer house with her son, she is portrayed by painter Lily Briscoe as a watery, dark triangle. Mr. Bankes, another guest at the summer house, is surprised that Mrs. Ramsay and her little boy who look like a Madonna with child can be reduced to a deep purple triangle. This scene in the novel was most likely inspired by Roger Fry’s Cubist version of the “Bridgewater Madonna,” a Madonna by Raphael on display in London in the Bridgewater House in 1917 (Reid 303).

As Roger Fry had lectured, written articles, and given interviews to expose how much photographic representation was at odds with real life, so Virginia Woolf now exposed how unrealistic the “frames” are that men and women put each other in. Woolf’s sensible feminism shows that the frames and the people who frame depend on each other, putting the blame with both males and females. Most male protagonists in To the Lighthouse depend on women for their self-image (Ruddick 35). Charles Tansley cannot enjoy the conversation at the dinner table until pressured by Mrs, Ramsey, Lily Briscoe gives him the limelight. Mrs. Ramsay also constantly assures Mr. Ramsay of his importance, like a mother encouraging her child. Mrs. Ramsay allows her husband to see himself as a “dying hero” who looks “from a mountain-top down the long wastes of the ages” and a “soldier” putting “his armour off” gazing “at his wife and son” when coming home to pay “homage to the beauty of the world” (42). But after Mr. Ramsay has become a widower, he pours his “self-pity…in pools” at Lily’s feet instead, who merely pulls her “skirts a little closer round her ankles” (166-7). Left to his own devices, he takes his children in a boat to the lighthouse to stage his own little drama, literally seeing himself as a “desolate man, widowed, bereft” (180).

The males like to “frame” Mrs. Ramsay as the prototype of a British beauty. Mr. Ramsay likes to see his wife as not very clever, but very beautiful. Mr. Bankes sees Mrs. Ramsay first as a kind of Greek goddess and later perceives her against the background of a masterpiece of Michael Angelo in a gilt frame. Even the usually cynical Charles Tansley feels excessively proud when a man stops digging in a drain to look at Mrs. Ramsay, whom he recalls standing in front of a picture of Queen Victoria. Indeed, her own daughter compares her to a queen and Mrs. Ramsay herself does feel that she has” the whole of the other sex under her protection…for their chivalry and valour, for the fact that they negotiated treaties, ruled India, controlled finance” (86). She will die, however, and when she dies, this whole way of life -the Victorian way- dies with her. The dinner party is her last great scene. She is the reigning Queen with her subjects around her, before the Fall of the Empire and before the Great War that would change everything.

After Mrs. Ramsay’s death, Lily is the only one who recognizes the frames set up for the subject she wants to paint. She sees the truth because she is a woman and an artist who is not only on the fringe of the Ramsay family, but is also at the edge of the lawn with her easel, and even on the fringe of Victorian society preferring painting to marriage. Lily tries to be blind to the outer beauty of Mrs. Ramsay and instead struggles like Roger Fry and Virginia Woolf, to get to the real truth under the surface. Lily even voices Fry’s and Woolf’s opinion that design or form should be “under” the over-all vision supporting it. Talking about her composition, she states that that surface should be “beautiful and bright…feathery and evanescent, one colour melting into another like the colours on a butterfly’s wing” yet beneath that surface “the fabric must be clamped together with bolts of iron” (198). To reduce Mrs. Ramsay to a purple triangle, Lily must be what Roger Fry called “detached.. She cannot let herself be overwhelmed by her deep love for her subject, just as much as Virginia Woolf could not get over-emotional about Mrs. Ramsay, who was based on her mother. Both writer and protagonist needed to step back, to look at the overall composition and texture of their picture from a distance.

The women in To the Lighthouse are indeed capable of seeing things from farther away, sometimes so far away that they don’t see themselves anymore, while the men see things from up close and always with themselves at the center of things (Ruddick 35). In this way, Mrs. Ramsay had stared at the beam of light from the lighthouse, which had reduced her to nothing. The things that women see though are usually vague, while the men see everything with clear outlines and literal details. Mrs. Ramsay, who is short-sighted and wears glasses, sees the lighthouse in an impressionistic way as “a silvery, misty-looking tower with a yellow eye that opened suddenly and softly,” while Mr. Ramsay with his sharp, little eagle eyes sees the lighthouse as “stark and straight” (218). Another aspect of this kind of perspective is that the vagueness and peacefulness of the distant view of the women is also associated with death, while the male vision is related to life and action. Both Lily painting on the shore and Cam Ramsay in a boat going to the lighthouse with her father, see the distance as peaceful and death-like. Yet when Mr. Ramsay tries to show Cam the points of the compass, she cannot see them to the utter amazement of her father and brother. Lily in the meantime feels more benevolent towards Mr. Ramsay, the farther away he is. While trying to bring the faraway Mrs. Ramsay closer when painting her picture, Lily muses that much depends on distance, once more echoing Roger Fry’s need for “detachment.”

The same technique of a distant, peaceful yet death-like point of view can be observed in the middle section of the book, called “Time Passes.” The first section, called “The Window” has a “fluid” perspective shifting smoothly from one point of view into another, yet always providing a clear, fairly detailed window on a person’s character. The last and third section, called “The Lighthouse,” more or less continues in the same vein as the first part to wrap up all the disparate odds and ends into one final vision. The center of the novel, the middle section, is more epic in approach. Yet the strange thing is that it portrays emptiness. The hub of the novel is a hole, an absence (Pearce 74). The absence of people from the summer house and the absence of Mrs. Ramsay from now on. In this significant section, time is accelerated, seasons and years follow each other in swift succession, reducing human agonies to parenthesized minor details. Whereas most of the novel is shown as a close-up of the various persons, “Time Passes” shows a distant vista of the setting. Like the misery often prerequisite to picturesqueness, the old rusty tools, the fallen basket and the overturned glass are not just painful reminders of a happier past, but also beautiful in their own melancholic right.

While Mrs. Ramsay is still alive, Lily is not mature enough and does not have enough courage yet or a deep enough need to go to the bottom of her emotions. It is not till after Mrs. Ramsay’s death and the Great War, however, that Lily tries to finish her painting. Then she is mature enough to delve so deep down into her dark self and the dark past that she comes close to that death-like state of self-abandonment to enable her to merge with the object she loves. Like Roger Fry and Virginia Woolf, she needs to fight her demons and be brutally honest with herself.

Lily has to bare the past till it hurts so that she can create an empty space. It is not till she has acknowledged the importance of the vacant space and bodily suffering, that she is ready for her vision (Smith 45). Her pain about the emptiness Mrs. Ramsay left is so deep that it hurts bodily, which is aptly symbolized by Macalister’s boy cutting a square out of a live fish to bait his hook and throwing back the mutilated but alive body into the sea. The boy’s cruel deed is also juxtaposed by Lily’s visceral realization that there can be no completeness without pain. There is no “positive” space without “negative” space; the one needs the other to define and/or complement it. In the same way that Mrs. Ramsay could only experience the wholeness of being together with her husband because of the pain of losing herself, so Lily can only experience a union with Mrs. Ramsay in her picture because of the pain of losing her. Lily has to acknowledge the importance of the empty space, for it is there that creation can take place and union can be achieved. She does this literally on her canvas as well and in one final stroke Lily captures the simultaneity of things far and close; while looking at the distant lighthouse that is reached at the exact same moment by the Ramsays, she draws a line in the center that unites all the separate elements into one comprehensive whole. It unites Lily and Mrs. Ramsay, life and death, Mr. Ramsay and his children, love and hate, the house and the lighthouse, and the far and the near in Lily’s final vision. And so too, the gist of all Roger Fry’s discussions with Virginia Woolf seemed to be united in this one novel, whose metaphor for the plot of the novel is a painting.

The Waves ~Post-Impressionism in Writing

On the eighth of October 1931, The Waves was published. It was Woolf’s most extreme Post-Impressionist novel with its abstraction of characters and plot and its emphasis on the effect of the overall feeling it produced. Vanessa Bell was quite impressed and overwhelmed by her sister’s ability to turn personal emotions (the Percival character who dies in India was based on their brother Thoby) into impersonal, almost abstract art. But Roger Fry, who had started doubting some of his own credos about Postimpressionism, was not sure about The Waves (Reid 345). Not much is known of the actual conversation that Fry had with Woolf after the publication. Yet Igor Anrep (the son of Fry’s partner Helen) reported Roger Fry shaking his head, saying that he feared that Woolf’s “abstract weaving of words” had not “achieved what she was trying to do” (Reid 345). Maybe this (Post-) Impressionist novel had come too late for Roger Fry, who constantly renewed himself and his opinions for fear of “fossilization.” It is true that Roger Fry had made a very public transition from Impressionism to Post-Impressionism with his exhibition back in 1910, while Virginia Woolf’s novel combined the two Schools of Art almost twenty years later. Yet it does not take away the tremendous achievement of a novel, whose “vision and design” are such a perfect blend.

The novel is structured by interludes interspersed with the monologues of her protagonists. These interludes are like a series of Impressionist studies of the light on the sea and land during the various points in the day. The objects stand for characters while the light stands for the passing time from childhood to death. Woolf uses painterly jargon and words to invite the reader to experience the scene pictorially. Bernard, the spokesman of the story, voices the idea behind the structure of the rest of the story, during the reunion of his friends at a French restaurant. He compares their friendship to a sort of seven-sided Cubist flower to which each individual brings their own point of view. In much the same way, the soliloquies of the main characters form the petals of the flower of the story. Yet despite the Impressionistic interludes and this “Cubist” structure of forming one picture from many-sided images, The Waves cannot be seen as pictorialist because too many confusing images “shortcircuit” (Torgovnick 130). Yet from this multitude of images, a perceptive reader is able to select and order a core of them, thereby constructing a largely abstract picture. It should be noted that the participation of the reader or viewer in a work of art is another very Post-Impressionist idea. Think for example of a Cubist portrait that can only be appreciated if the “pieces” the viewer is offered are linked in some way by the viewer’s mind. So even though Roger Fry was not convinced that Virginia Woolf had managed to write a truly great Post-Impressionist novel, the things that he had taught her about Impressionism and Cubism formed the basis of this novel.

On the whole, the images connected to the protagonist are also far more abstract than in the previous books. The first half of the book sketches the characters, through the scraps of thoughts they entrust to the reader. The reader can piece together that Susan is Mother Earth, Jinny’s element is Fire and Rhoda has no element and will later commit suicide. The poor, Australian Louis aspires to the British upper classes, Neville typecasts himself as the vulnerable poet, and easy-going Bernard seems an everyman. The men are all united by the image of the British Empire. They dream of ruling it, while the women perpetuate their dreams by complying with them. The end of this white, male-dominated British Empire is represented by Percival, who dies half-way through the novel in India. Bernard, the spokesperson of the group, is granted the elegy. He conjures up an over-blown romantic picture describing Percival as the questing knight of the round table, who would have helped all those poor Indians. As Roger Fry wanted to rid painting of photographic representation, so Virginia Woolf wanted to purge literature of the romanticism and fake realism that had nothing to do with real human feelings in the real world.

As in Mrs. Dalloway, nature is described in this novel as female, starting with an interlude describing the rising sun as a woman holding up a lamp. But when Bernard describes his commuter train into London, a “female, majestic” city, as a male “missile exploding in her flanks” (111), the Futuristic violence reminds of rape. The male myth of Elvedon of the beginning of the story comes to mind. Bernard told Susan about a mysterious garden with a writing lady in a window. Bernard perceived this as menacing, something outside his male control. According to Richard Pearce, it symbolizes his fear of female authority (Pearce 78). At the end of the novel, Bernard takes over. The story about men and women is turned into a story about him. He displaces the female authoress and changes the Aurora myth, for he turns the female sun into a male sun again. Even though he sees himself as many-sided and androgenous, in the end he personifies the typical, white, British upper-class male. He rides against death in the same way he imagines Percival did.

The End of the Tremendous Struggle to Hold on to their Vision

Virginia Woolf and Roger Fry would go their separate ways during the following decade. Fry felt that morality had nothing to do with art and had insisted over and over again that art should be detached. But under her husband’s influence and with the threat of war, Virginia Woolf now started voicing her political and feminist opinions more and more in her writing. Even though the art critic and the writer continued to be the best of friends, they both embarked on projects of their own. Woolf wrote many short pieces and some experimental novels. And Fry produced two of his most notable works: Reflections on British Painting (1934), which went on in the same vein as his conversations with Woolf and his earlier writings, and The Last Lectures (1939), which he delivered as a Slade Professor of Fine Arts at Cambridge before he died.

Despite earlier health problems, Roger Fry died shockingly suddenly. It shook Virginia Woolf to the core, more so than the death of any other friends. She had been saddened in 1932 by Lytton Strachy’s death for instance, but it did not have the same effect on her. Being a writer, she immediately thought of doing a biography on the man she owed so much to. Initial problems with the “design” and any surviving relatives that could be shocked by too frank revelations were ultimately disregarded, to start the immense work of going through all her friend’s letters and notes. Though occasionally overwhelmed and depressed by the task she had set herself, she seemed to have embarked on a posthumous love affair with her subject. The following year Roger Fry: A Biography was published. Despite its amazingly conventional “design,” the book’s “significant form,” its over-all effect on the reader is extremely successful. Woolf manages to communicate the enthusiasm, the passion, and courageous honesty of Roger Fry’s vision, because she had shared it with him.

The next year, she wrote her final novel titled Between the Acts. In it, several of the earlier, by Roger Fry-inspired notions return. As the interpolations in italics about the rising and setting sun had framed and structured The Waves, so here Miss La Trobe’s play is interpolated in italics. The lady’s name -a trope- does of course not only refer to figures of speech, but to seeing and how we put in words what we see. The notion of representation is parodied as the actors show the audience themselves by holding mirrors in front of them. This also recalls Roger Fry’s own idea expressed in “An Essay in Aesthetics” that looking at a scene in a mirror makes it easier to “abstract ourselves” from life and look at what we see in the mirror in a more detached way (Fry 19-20). Between the Acts also displays the same desire for the reader to respond and participate, as a Cubist painting that forces the viewer to construct an intelligible picture out of fragments. The point on which Woolf now diverged from Roger Fry’s teachings, was in fact to her credit; she united the artistic, depersonalized structure that Fry preferred with the political relevance that he thought unnecessary in art and had labelled “moralizing” or “ethical.” For the setting and timing of an England over which threatening bombers fly in June 1939, shows how art can serve as a defense against the threat of war. In her own life, however, her art could no longer shield Virginia Woolf from the enemy. The fear of the Nazis as well as her own private “demons” proved too much for her so that she drowned herself in the river Ouse on the day the Germans were supposed to invade England.

Despite their privileged upbringing, both Virginia Woolf and Roger Fry did not have an easy life. Both came from well-to-do families that were firmly rooted in the British Empire, but they had the courage to criticize the society they belonged to and to go their own ways. Woolf suggested in her biography of Fry that he had to swim against the current of his parents’ Quaker background and the “Philistines.” His professional life went over a bumpy road as well; his parents sent him to study science, so it took courage to declare his love for art and actually make his career out of his hobby. He traveled alone by public transportation to the remotest places to look at, photograph, or pick up works of art for his lectures or reviews. He was refused several posts at museums and universities he had hoped for, and he had to struggle to keep his Omega workshop for artists afloat during the First World War. In addition, his first wife went mad, he was dumped by Vanessa Bell, and only seemed to find some happiness late in life with Helen Anrep. So, for a large part of his life he was alone, courageously fighting for his ideals, trying to live life to the fullest without “falling into the great sin of Accidia” (Biography 215). We hear echoes of Woolf’s own struggle with the “hairy monsters” of her psyche that constantly threatened her sanity. She spent months in solitary confinement, in hospitals, bravely fighting to ward off madness and to pursue what she believed in.

In To the Lighthouse, Lily Briscoe must fight clichés or preconceived notions in order to portray her subject the way she envisages it, despite contrary opinions of others. She must go deep down into the “dark passage,” the place where she creates her art and where she wrestles with her “demons” (25). It is a tremendous struggle to keep faith in her own vision. While Roger Fry seemed stoic compared to the bundle of nerves that Virginia Woolf was, both suffered in the same way as Lily to attain their vision. Against the current of the time, against the establishment, sometimes against themselves, they had to “swim” to reach the golden pond of Post-Impressionism. The older, male art critic initially lead the inexperienced female novelist. But soon she could “swim” on her own and often abandoned the school to explore other waters. Despite the odds, neither of them ever shunned the “dark passage.” They were true to their principles and true to themselves. At the end of their lives, they could lay down their brush and pen “in extreme fatigue” to say: “I have had my vision” (224).

Works Cited:

DeSalvo, Louise A. Virginia Woolf’s First Voyage – A Novel in the Making. New Jersey, Rowan and Littlefield, 1980.

Fry, Roger. Vision and Design. New York, Peter Smith, 1947.

Handley, William R. “the Housemaid and the Kitchen Table: Incorporating the Frame in To the Lighthouse.” Twentieth Century Literature. Spring 1994. 15-41.

Kapur, Vijay. Virginia Woolf’s Vision of Life and her Search for Significant Form – A Study in the Shaping Vision. New Jersey, Humanities Press Inc, 1980.

Lee, Hermione. Virginia Woolf. New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1997.

Pearce, Richard. “Virginia Woolf’s Struggle with Authority.” Image and Ideology in Modern/Postmodern Discourse. Albany, State University of New York Press, 1991:69-83.

Reid, Panthea. Art and Affection – A Life of Virginia Woolf. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1996.

Ruddick, Lisa Cole. The Seen and the Unseen: Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1977.

Smith, Grady. “Virginia Woolf: The Narrow Bridge of Art.” Modern Age. Fall 1993: 38-46.

Stansky, Peter. On or about December 1910 – Early Bloomsbury and its Intimate World. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1996.

Torgovnick, Marianna. The Visual Arts, Pictorialism and the Novel – James, Lawrence and Woolf. Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1985.

Woolf, Virginia. “Neo-Impressionism and Literature.” Times Literary Supplement 5. July 1917, 319.

Woolf, Virginia. “Kew Gardens.” New York, Harcourt Brace & Co., 1985.

Woolf, Virginia. Between the Acts. New York, Harcourt Brace & Co., 1941.

Woolf, Virginia. Collected Essays. London, The Hogarth Press, 1966.

Woolf, Virginia. Mrs. Dalloway. London, The Hogarth Press, 1925.

Woolf, Virginia. Roger Fry – A Biography. New York, Harcourt Brace & Co., 1940.

Woolf, Virginia. The Diary of Virginia Woolf (Five Volumes). New York, Harcourt Brace & Co, 1977-84.

Woolf, Virginia. The Letters of Virginia Woolf (Five Volumes). New York, Harcourt Brace & Co., 1978.

Woolf, Virginia. The Voyage Out. New York, Harcourt Brace & Co, 1915.

Woolf, Virginia. The Waves. New York, Harcourt Brace & Co., 1970.

Woolf, Virginia. To the Lighthouse. London, Harper Collins, 1977.

MORE essays

discover

JOIN MY NEWSLETTER

To receive announcements about new blogs, images, essays, lectures, and novels, please sign up.